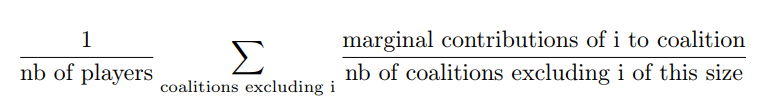

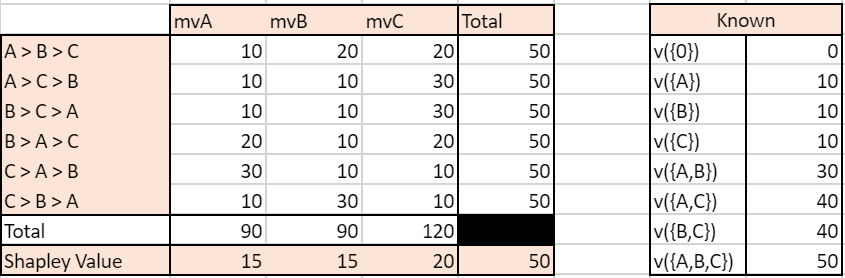

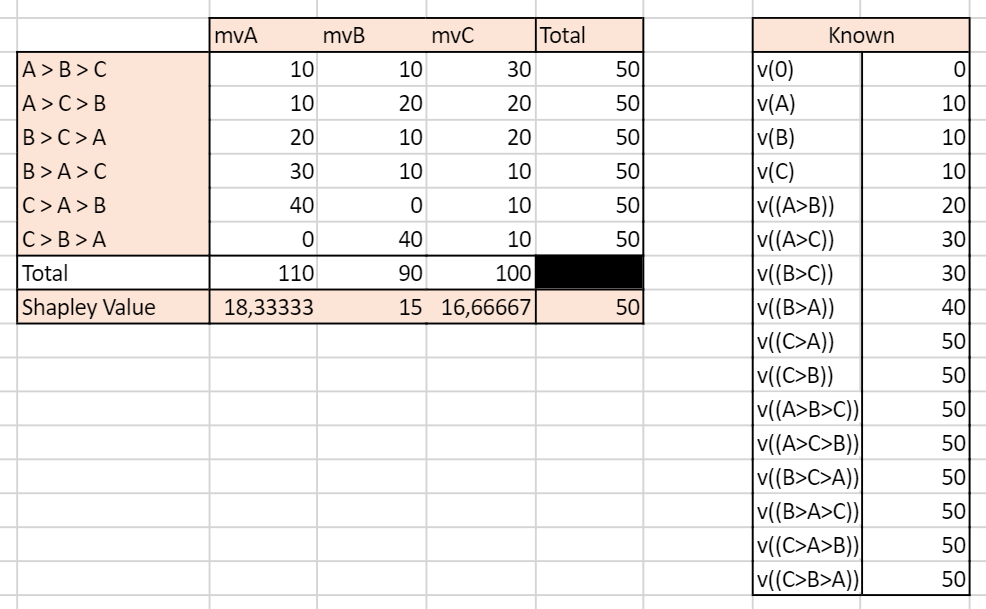

Einleitung

Aufgrund vielfältiger potenzieller Geschäftschancen, die Machine Learning bietet, arbeiten mittlerweile viele Unternehmen an Initiativen für datengetriebene Innovationen. Dabei gründen sie Analytics-Teams, schreiben neue Stellen für Data Scientists aus, bauen intern Know-how auf und fordern von der IT-Organisation eine Infrastruktur für “heavy” Data Engineering & Processing samt Bereitstellung einer Analytics-Toolbox ein. Für IT-Architekten warten hier spannende Herausforderungen, u.a. bei der Zusammenarbeit mit interdisziplinären Teams, deren Mitglieder unterschiedlich ausgeprägte Kenntnisse im Bereich Machine Learning (ML) und Bedarfe bei der Tool-Unterstützung haben. Einige Überlegungen sind dabei: Sollen Data Scientists mit ML-Toolkits arbeiten und eigene maßgeschneiderte Algorithmen nur im Ausnahmefall entwickeln, damit später Herausforderungen durch (unkonventionelle) Integrationen vermieden werden? Machen ML-Funktionen im seit Jahren bewährten ETL-Tool oder in der Datenbank Sinn? Sollen ambitionierte Fachanwender künftig selbst Rohdaten aufbereiten und verknüpfen, um auf das präparierte Dataset einen populären Algorithmus anzuwenden und die Ergebnisse selbst interpretieren? Für die genannten Fragestellungen warten junge & etablierte Software-Hersteller sowie die Open Source Community mit “All-in-one”-Lösungen oder Machine Learning-Erweiterungen auf. Vor dem Hintergrund des Data Science Prozesses, der den Weg eines ML-Modells von der experimentellen Phase bis zur Operationalisierung beschreibt, vergleicht dieser Artikel ausgewählte Ansätze (Notebooks für die Datenanalyse, Machine Learning-Komponenten in ETL- und Datenvisualisierungswerkzeugen vs. Speziallösungen für Machine Learning) und betrachtet mögliche Einsatzbereiche und Integrationsaspekte.

Data Science Prozess und Teams

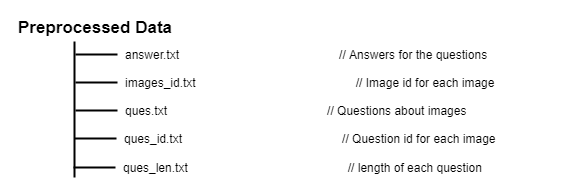

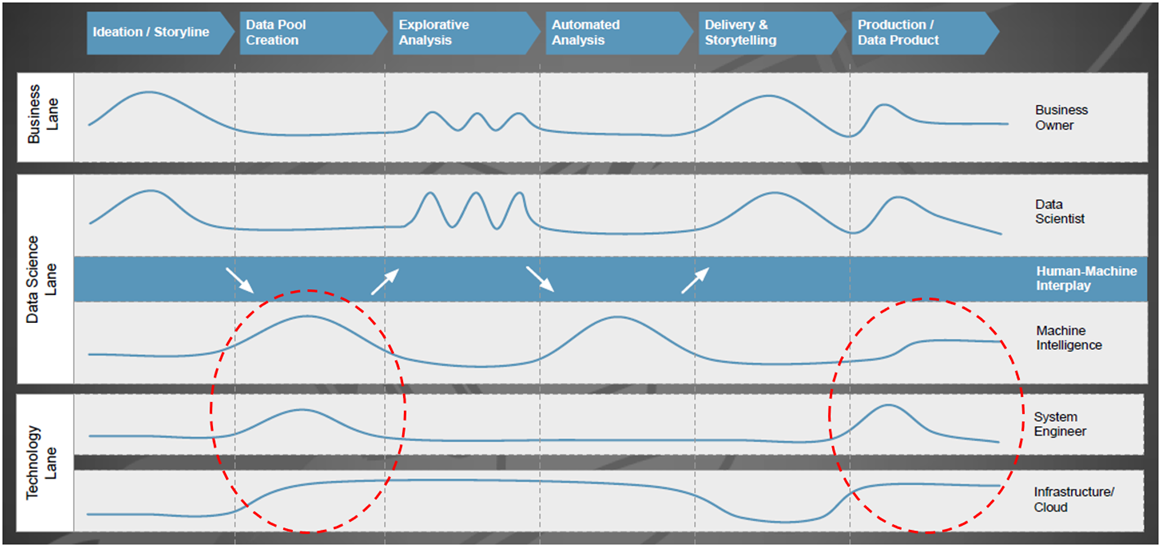

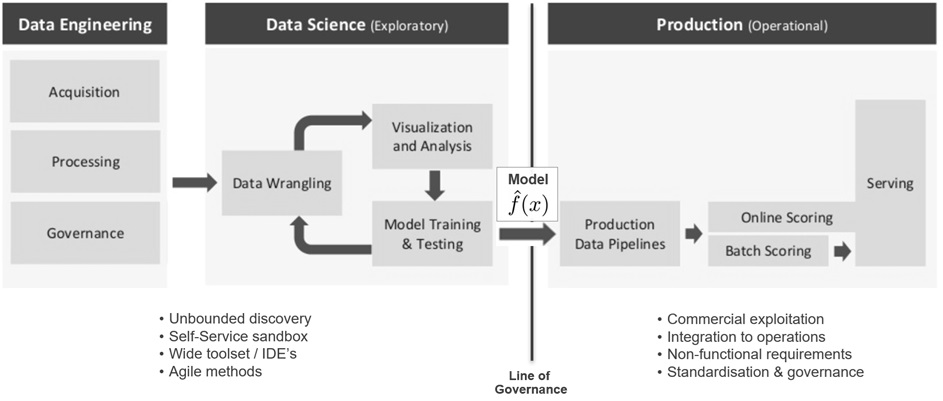

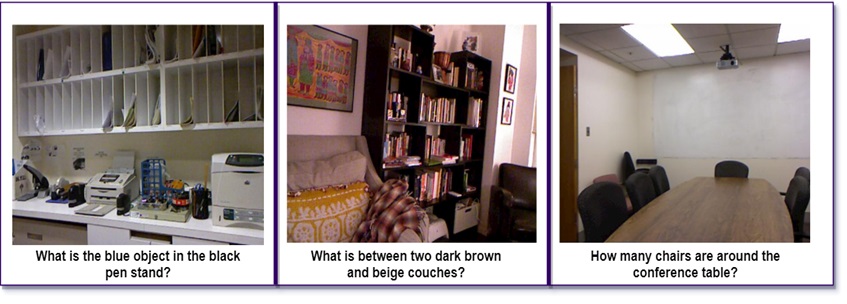

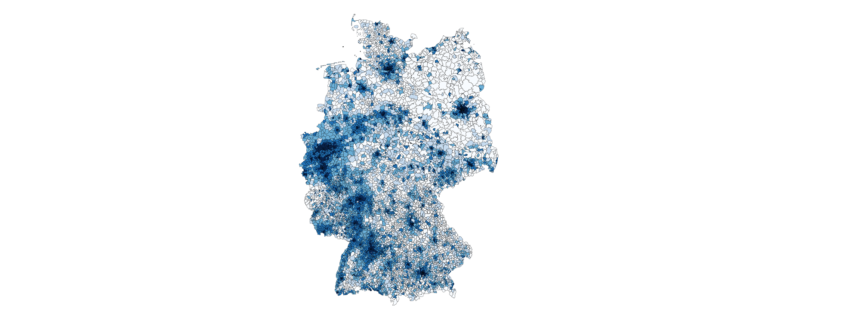

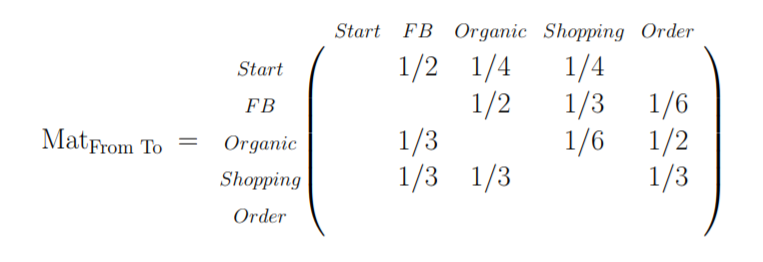

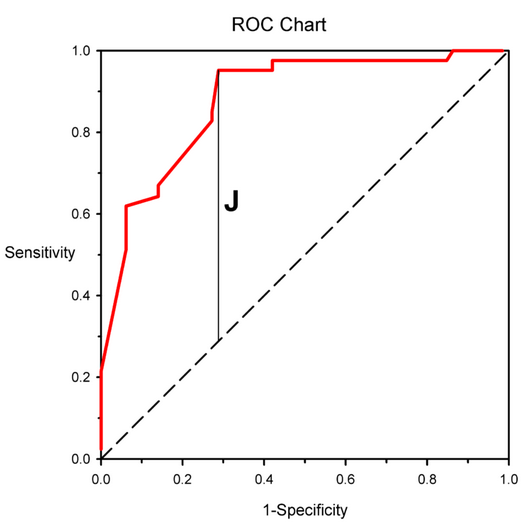

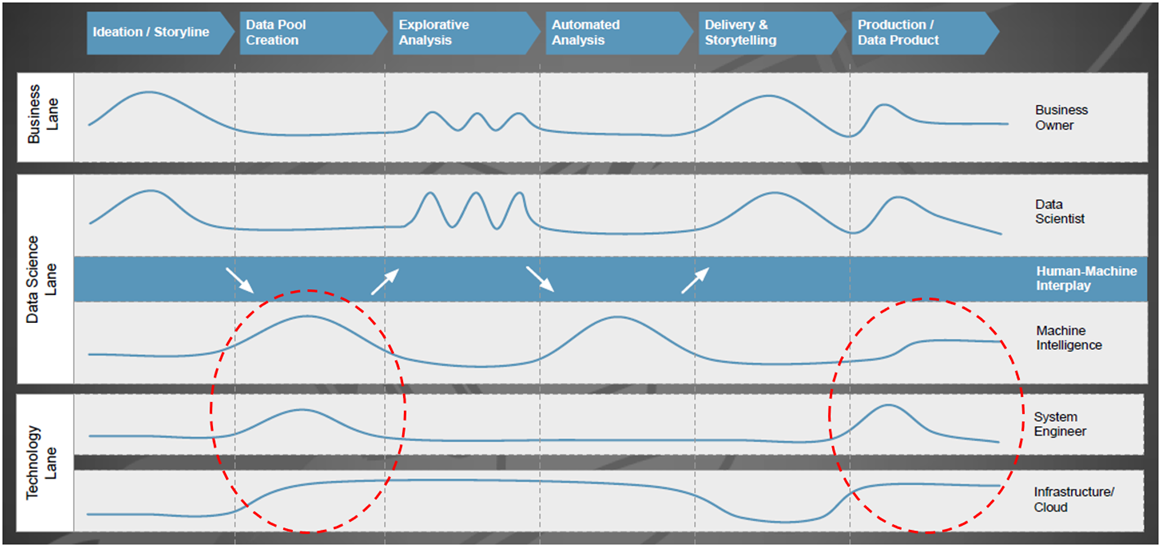

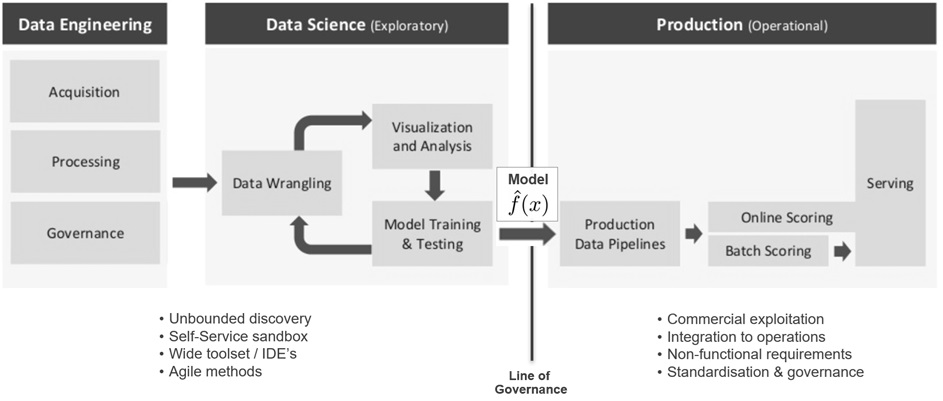

Im Zuge des Big Data-Hypes kamen neben Design-Patterns für Big Data- und Analytics-Architekturen auch Begriffsdefinitionen auf, die Disziplinen wie Datenintegration von Data Engineering und Data Science voneinander abgrenzen [1]. Prozessmodelle, wie das ab 1996 im Rahmen eines EU-Förderprojekts entwickelte CRISP-DM (CRoss-Industry Standard Process for Data Mining) [2], und Best Practices zur Organisation erfolgreich arbeitender Data Science Teams [3] weisen dabei die Richtung, wie Unternehmen das Beste aus den eigenen Datenschätzen herausholen können. Die Disziplin Data Science beschreibt den, an ein wissenschaftliches Vorgehen angelehnten, Prozess der Nutzung von internen und externen Datenquellen zur Optimierung von Produkten, Dienstleistungen und Prozessen durch die Anwendung statistischer und mathematischer Modelle. Bild 1 stellt in einem Schwimmbahnen-Diagramm einzelne Phasen des Data Science Prozesses den beteiligten Funktionen gegenüber und fasst Erfahrungen aus der Praxis zusammen [5]. Dabei ist die Intensität bei der Zusammenarbeit zwischen Data Scientists und System Engineers insbesondere bei Vorbereitung und Bereitstellung der benötigten Datenquellen und später bei der Produktivsetzung des Ergebnisses hoch. Eine intensive Beanspruchung der Server-Infrastruktur ist in allen Phasen gegeben, bei denen Hands-on (und oft auch massiv parallel) mit dem Datenpool gearbeitet wird, z.B. bei Datenaufbereitung, Training von ML Modellen etc.

Abbildung 1: Beteiligung und Interaktion von Fachbereichs-/IT-Funktionen mit dem Data Science Team

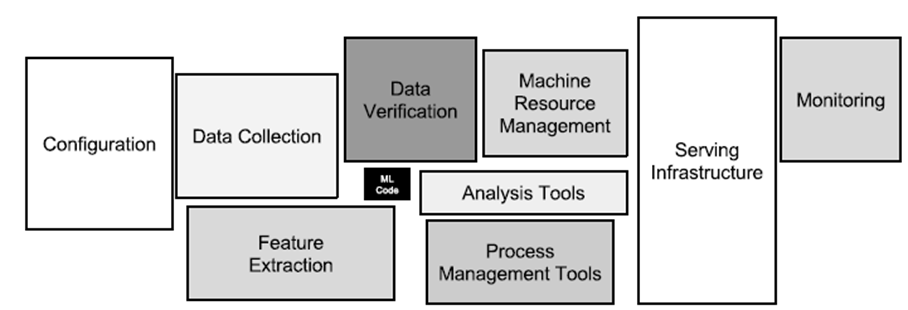

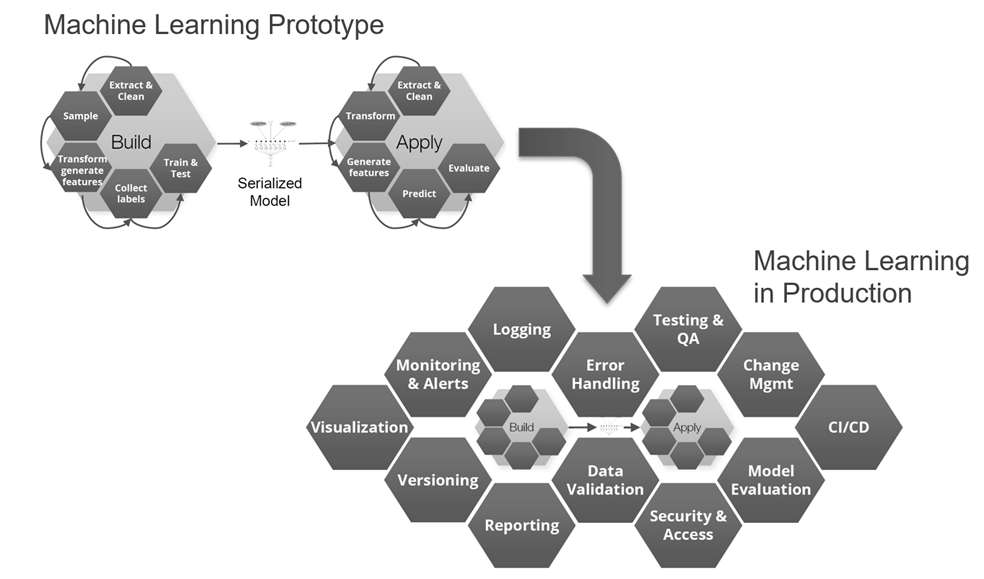

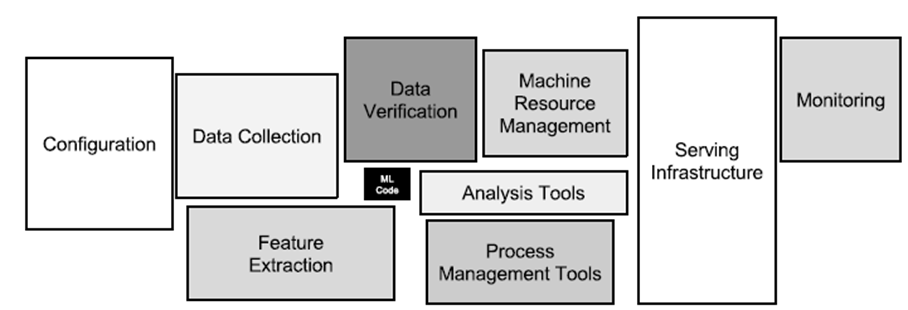

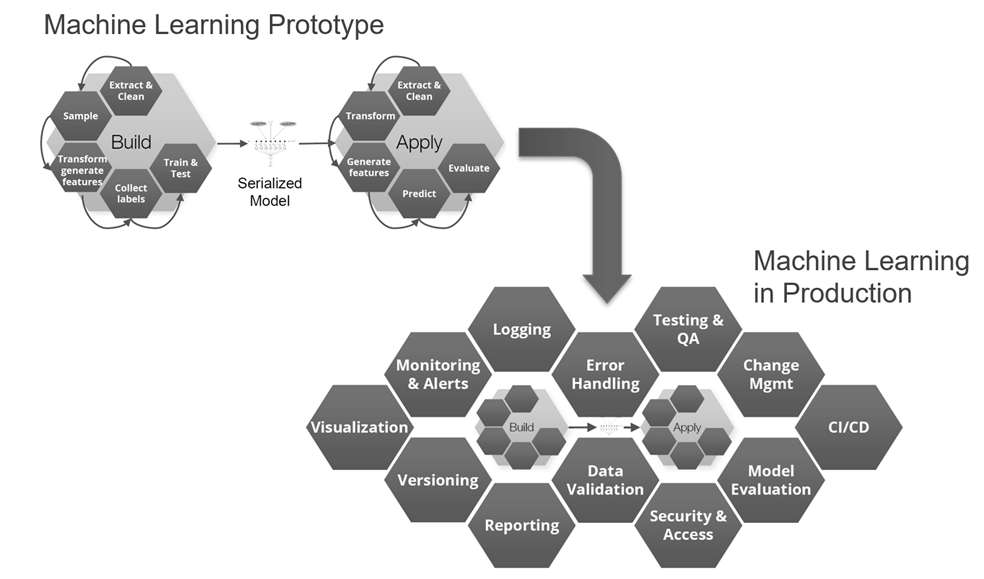

Mitarbeiter vom Technologie-Giganten Google haben sich reale Machine Learning-Systeme näher angesehen und festgestellt, dass der Umsetzungsaufwand für den eigentlichen Kern (= der ML-Code, siehe den kleinen schwarzen Kasten in der Mitte von Bild 2) gering ist, wenn man dies mit der Bereitstellung der umfangreichen und komplexen Infrastruktur inklusive Managementfunktionen vergleicht [4].

Abbildung 2: Versteckte technische Anforderungen in maschinellen Lernsystemen

Konzeptionelle Architektur für Machine Learning und Analytics

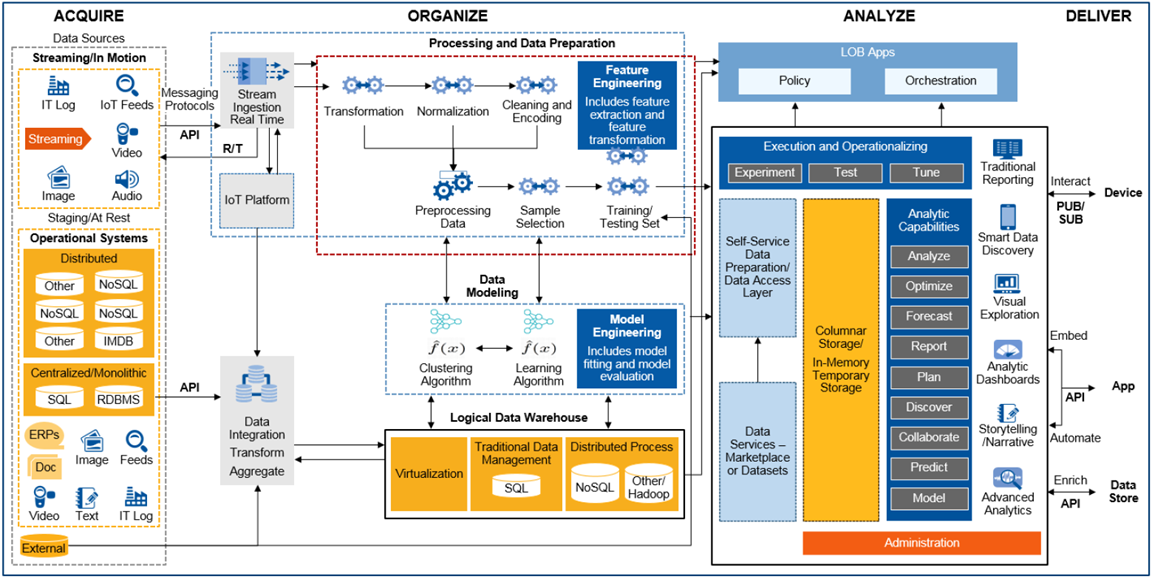

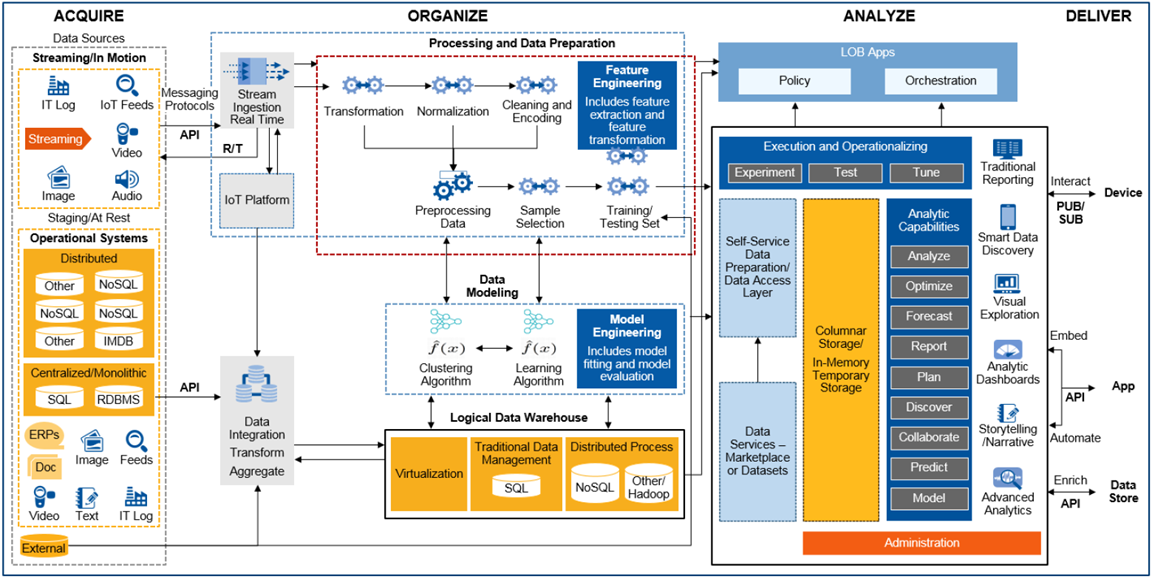

Die Nutzung aller verfügbaren Daten für Analyse, Durchführung von Data Science-Projekten, mit den daraus resultierenden Maßnahmen zur Prozessoptimierung und -automatisierung, bedeutet für Unternehmen sich neuen Herausforderungen zu stellen: Einführung neuer Technologien, Anwendung komplexer mathematischer Methoden sowie neue Arbeitsweisen, die in dieser Form bisher noch nicht dagewesen sind. Für IT-Architekten gibt es also reichlich Arbeit, entweder um eine Data Management-Plattform neu aufzubauen oder um das bestehende Informationsmanagement weiterzuentwickeln. Bild 3 zeigt hierzu eine vierstufige Architektur nach Gartner [6], ausgerichtet auf Analytics und Machine Learning.

Abbildung 3: Konzeptionelle End-to-End Architektur für Machine Learning und Analytics

Was hat sich im Vergleich zu den traditionellen Data Warehouse- und Business Intelligence-Architekturen aus den 1990er Jahren geändert? Denkt man z.B. an die Präzisionsfertigung eines komplexen Produkts mit dem Ziel, den Ausschuss weiter zu senken und in der Produktionslinie eine höhere Produktivitätssteigerung (Kennzahl: OEE, Operational Equipment Efficiency) erzielen zu können: Die an der Produktherstellung beteiligten Fertigungsmodule (Spezialmaschinen) messen bzw. detektieren über zahlreiche Sensoren Prozesszustände, speicherprogrammierbare Steuerungen (SPS) regeln dazu die Abläufe und lassen zu Kontrollzwecken vom Endprodukt ein oder mehrere hochauflösende Fotos aufnehmen. Bei diesem Szenario entsteht eine Menge interessanter Messdaten, die im operativen Betrieb häufig schon genutzt werden. Z.B. für eine Echtzeitalarmierung bei Über- oder Unterschreitung von Schwellwerten in einem vorher definierten Prozessfenster. Während früher vielleicht aus Kostengründen nur Statusdaten und Störungsinformationen den Weg in relationale Datenbanken fanden, hebt man heute auch Rohdaten, z.B. Zeitreihen (Kraftwirkung, Vorschub, Spannung, Frequenzen,…) für die spätere Analyse auf.

Bezogen auf den Bereich Acquire bewältigt die IT-Architektur in Bild 3 nun Aufgaben, wie die Übernahme und Speicherung von Maschinen- und Sensordaten, die im Millisekundentakt Datenpunkte erzeugen. Während IoT-Plattformen das Registrieren, Anbinden und Management von Hunderten oder Tausenden solcher datenproduzierender Geräte („Things“) erleichtern, beschreibt das zugehörige IT-Konzept den Umgang mit Protokollen wie MQTT, OPC-UA, den Aufbau und Einsatz einer Messaging-Plattform für Publish-/Subscribe-Modelle (Pub/Sub) zur performanten Weiterverarbeitung von Massendaten im JSON-Dateiformat. Im Bereich Organize etablieren sich neben relationalen Datenbanken vermehrt verteilte NoSQL-Datenbanken zum Persistieren eingehender Datenströme, wie sie z.B. im oben beschriebenen Produktionsszenario entstehen. Für hochauflösende Bilder, Audio-, Videoaufnahmen oder andere unstrukturierte Daten kommt zusätzlich noch Object Storage als alternative Speicherform in Frage. Neben der kostengünstigen und langlebigen Datenaufbewahrung ist die Möglichkeit, einzelne Objekte mit Metadaten flexibel zu beschreiben, um damit später die Auffindbarkeit zu ermöglichen und den notwendigen Kontext für die Analysen zu geben, hier ein weiterer Vorteil. Mit dem richtigen Technologie-Mix und der konsequenten Umsetzung eines Data Lake– oder Virtual Data Warehouse-Konzepts gelingt es IT-Architekten, vielfältige Analytics Anwendungsfälle zu unterstützen.

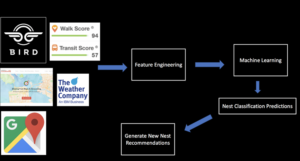

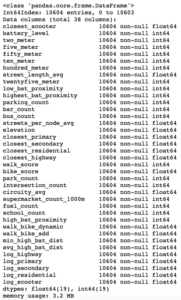

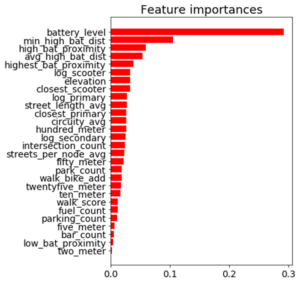

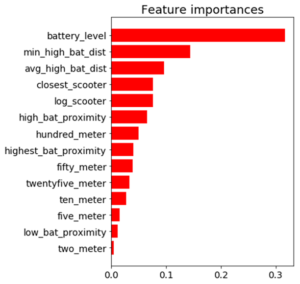

Im Rahmen des Data Science Prozesses spielt, neben der sicheren und massenhaften Datenspeicherung sowie der Fähigkeit zur gleichzeitigen, parallelen Verarbeitung großer Datenmengen, das sog. Feature-Engineering eine wichtige Rolle. Dazu wieder ein Beispiel aus der maschinellen Fertigung: Mit Hilfe von Machine Learning soll nach unbekannten Gründen für den zu hohen Ausschuss gefunden werden. Was sind die bestimmenden Faktoren dafür? Beeinflusst etwas die Maschinenkonfiguration oder deuten Frequenzveränderungen bei einem Verschleißteil über die Zeit gesehen auf ein Problem hin? Maschine und Sensoren liefern viele Parameter als Zeitreihendaten, aber nur einige davon sind – womöglich nur in einer bestimmten Kombination – für die Aufgabenstellung wirklich relevant. Daher versuchen Data Scientists bei der Feature-Entwicklung die Vorhersage- oder Klassifikationsleistung der Lernalgorithmen durch Erstellen von Merkmalen aus Rohdaten zu verbessern und mit diesen den Lernprozess zu vereinfachen. Die anschließende Feature-Auswahl wählt bei dem Versuch, die Anzahl von Dimensionen des Trainingsproblems zu verringern, die wichtigste Teilmenge der ursprünglichen Daten-Features aus. Aufgrund dieser und anderer Arbeitsschritte, wie z.B. Auswahl und Training geeigneter Algorithmen, ist der Aufbau eines Machine Learning Modells ein iterativer Prozess, bei dem Data Scientists dutzende oder hunderte von Modellen bauen, bis die Akzeptanzkriterien für die Modellgüte erfüllt sind. Aus technischer Sicht sollte die IT-Architektur auch bei der Verwaltung von Machine Learning Modellen bestmöglich unterstützen, z.B. bei Modell-Versionierung, -Deployment und -Tracking in der Produktionsumgebung oder bei der Automatisierung des Re-Trainings.

Die Bereiche Analyze und Deliver zeigen in Bild 3 einige bekannte Analysefähigkeiten, wie z.B. die Bereitstellung eines Standardreportings, Self-service Funktionen zur Geschäftsplanung sowie Ad-hoc Analyse und Exploration neuer Datasets. Data Science-Aktivitäten können etablierte Business Intelligence-Plattformen inhaltlich ergänzen, in dem sie durch neuartige Kennzahlen, das bisherige Reporting „smarter“ machen und ggf. durch Vorhersagen einen Blick in die nahe Zukunft beisteuern. Machine Learning-as-a-Service oder Machine Learning-Produkte sind alternative Darreichungsformen, um Geschäftsprozesse mit Hilfe von Analytik zu optimieren: Z.B. integriert in einer Call Center-Applikation, die mittels Churn-Indikatoren zu dem gerade anrufenden erbosten Kunden einen Score zu dessen Abwanderungswilligkeit zusammen mit Handlungsempfehlungen (Gutschein, Rabatt) anzeigt. Den Kunden-Score oder andere Risikoeinschätzungen liefert dabei eine Service Schnittstelle, die von verschiedenen unternehmensinternen oder auch externen Anwendungen (z.B. Smartphone-App) eingebunden und in Echtzeit angefragt werden kann. Arbeitsfelder für die IT-Architektur wären in diesem Zusammenhang u.a. Bereitstellung und Betrieb (skalierbarer) ML-Modelle via REST API’s in der Produktionsumgebung inklusive Absicherung gegen unerwünschten Zugriff.

Ein klassischer Ansatz: Datenanalyse und Machine Learning mit Jupyter Notebook & Python

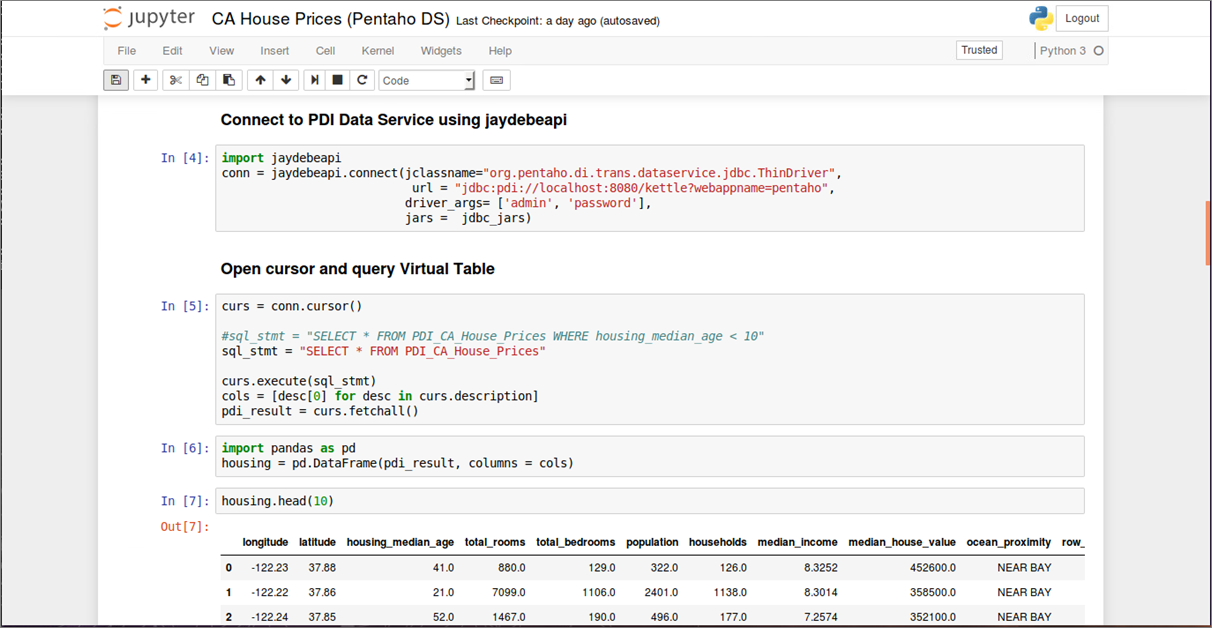

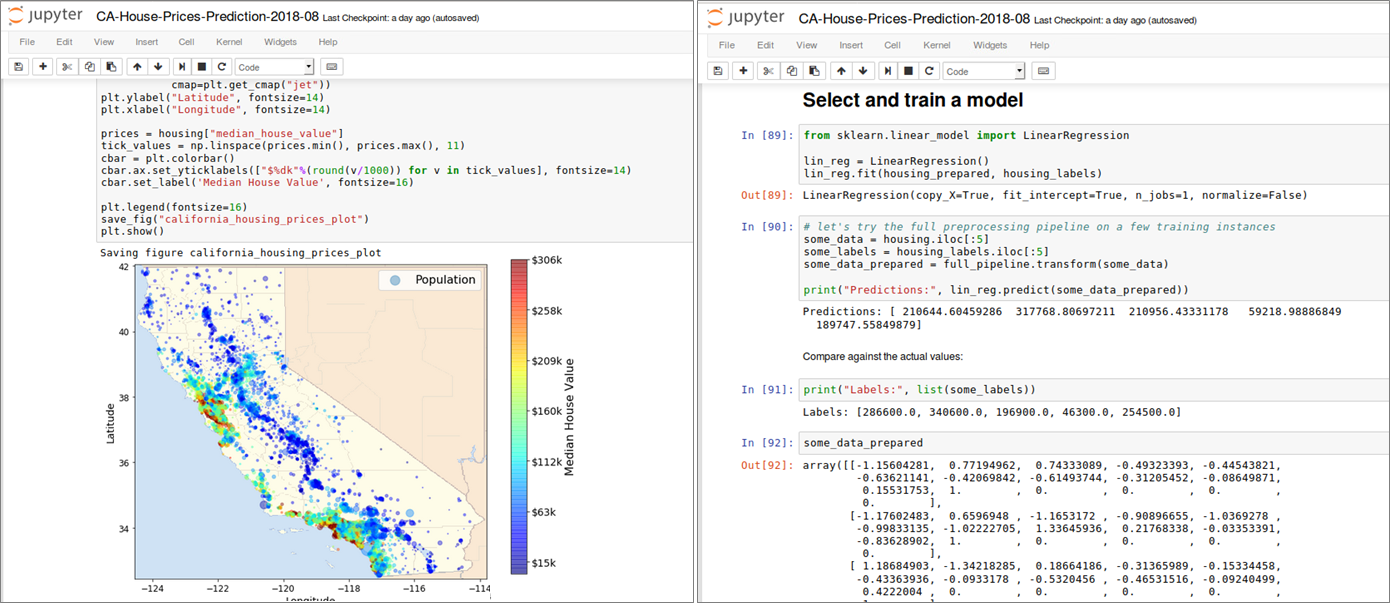

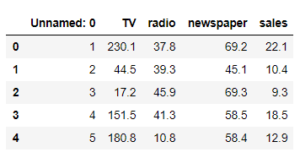

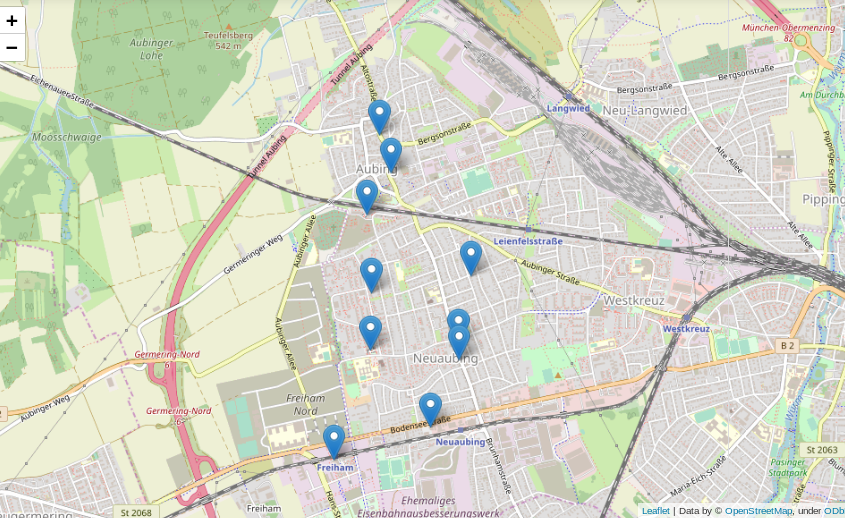

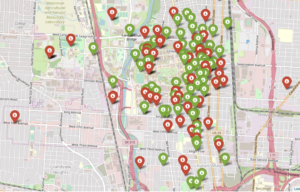

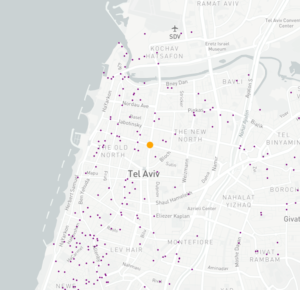

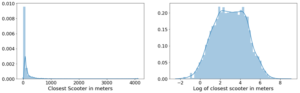

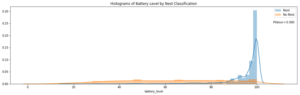

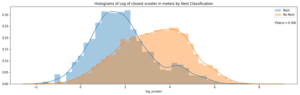

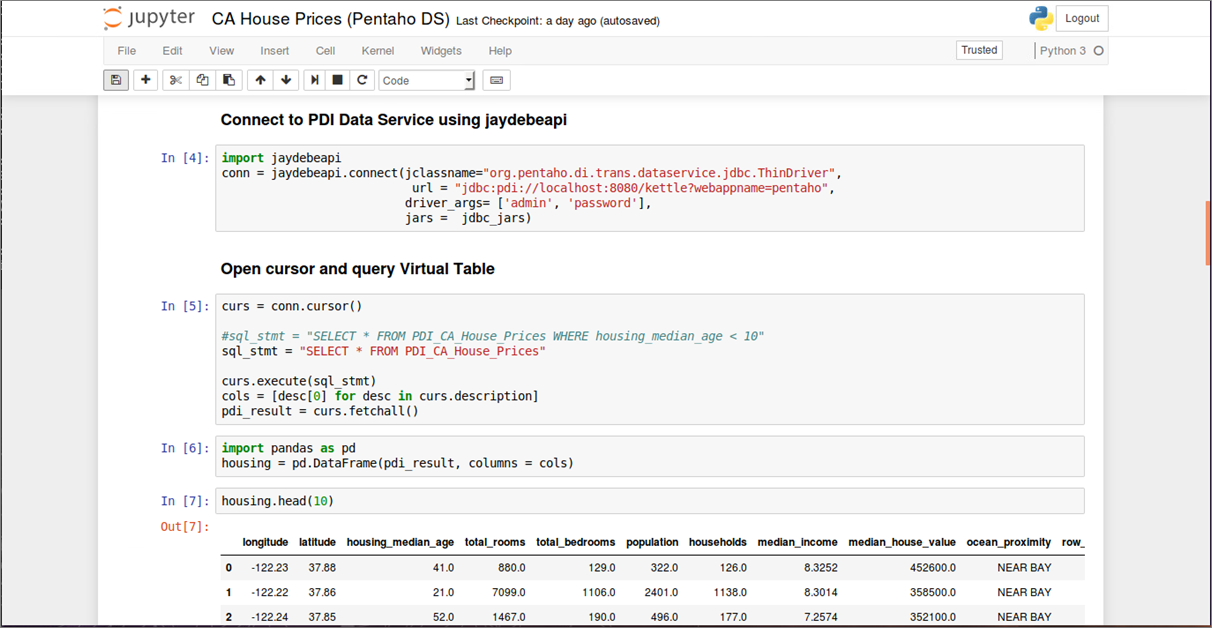

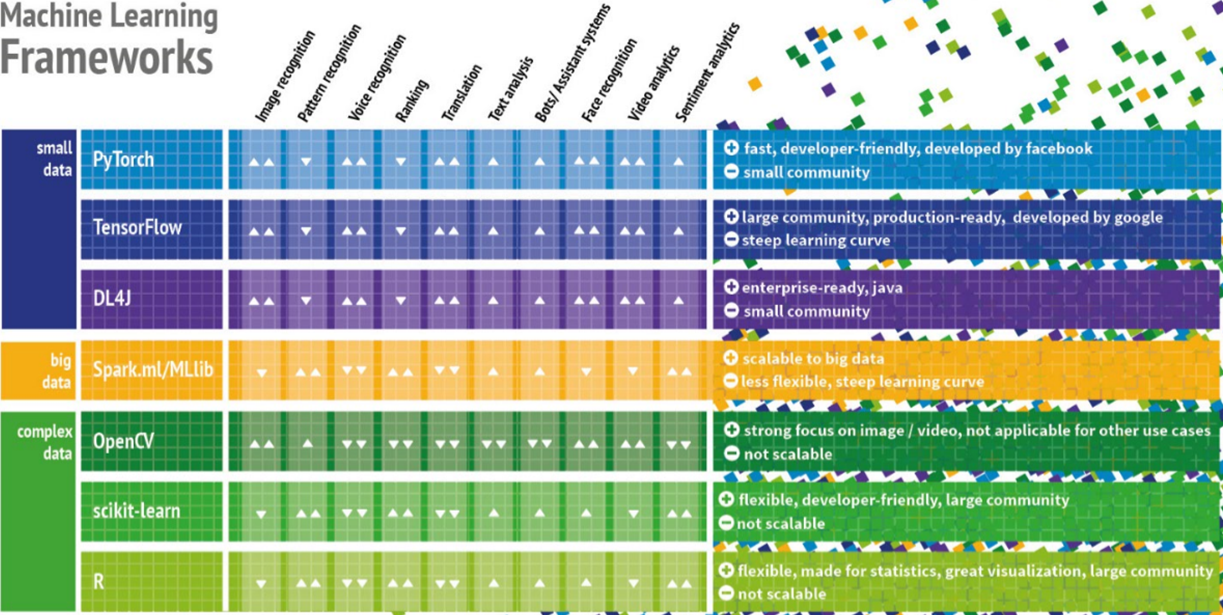

Jupyter ist ein Kommandozeileninterpreter zum interaktiven Arbeiten mit der Programmiersprache Python. Es handelt sich dabei nicht nur um eine bloße Erweiterung der in Python eingebauten Shell, sondern um eine Softwaresuite zum Entwickeln und Ausführen von Python-Programmen. Funktionen wie Introspektion, Befehlszeilenergänzung, Rich-Media-Einbettung und verschiedene Editoren (Terminal, Qt-basiert oder browserbasiert) ermöglichen es, Python-Anwendungen als auch Machine Learning-Projekte komfortabel zu entwickeln und gleichzeitig zu dokumentieren. Datenanalysten sind bei der Arbeit mit Juypter nicht auf Python als Programmiersprache begrenzt, sondern können ebenso auch sog. Kernels für Julia, R und vielen anderen Sprachen einbinden. Ein Jupyter Notebook besteht aus einer Reihe von “Zellen”, die in einer Sequenz angeordnet sind. Jede Zelle kann entweder Text oder (Live-)Code enthalten und ist beliebig verschiebbar. Texte lassen sich in den Zellen mit einer einfachen Markup-Sprache formatieren, komplexe Formeln wie mit einer Ausgabe in LaTeX darstellen. Code-Zellen enthalten Code in der Programmiersprache, die dem aktiven Notebook über den entsprechenden Kernel (Python 2 Python 3, R, etc.) zugeordnet wurde. Bild 4 zeigt auszugsweise eine Analyse historischer Hauspreise in Abhängigkeit ihrer Lage in Kalifornien, USA (Daten und Notebook sind öffentlich erhältlich [7]). Notebooks erlauben es, ganze Machine Learning-Projekte von der Datenbeschaffung bis zur Evaluierung der ML-Modelle reproduzierbar abzubilden und lassen sich gut versionieren. Komplexe ML-Modelle können in Python mit Hilfe des Pickle Moduls, das einen Algorithmus zur Serialisierung und De-Serialisierung implementiert, ebenfalls transportabel gemacht werden.

Abbildung 4: Datenbeschaffung, Inspektion, Visualisierung und ML Modell-Training in einem Jupyter Notebook (Pro-grammiersprache: Python)

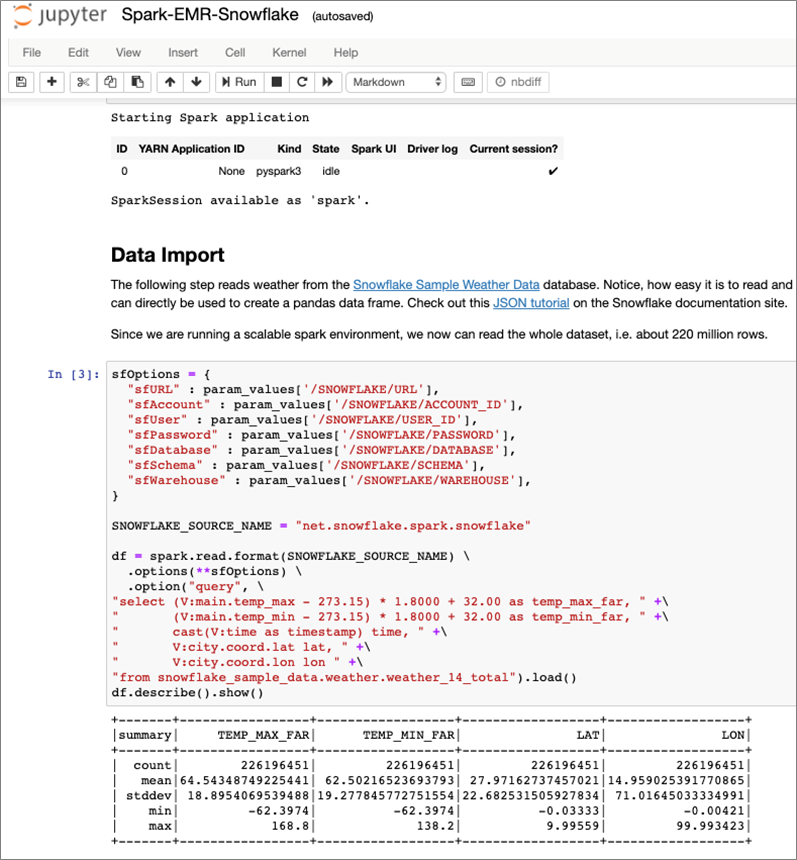

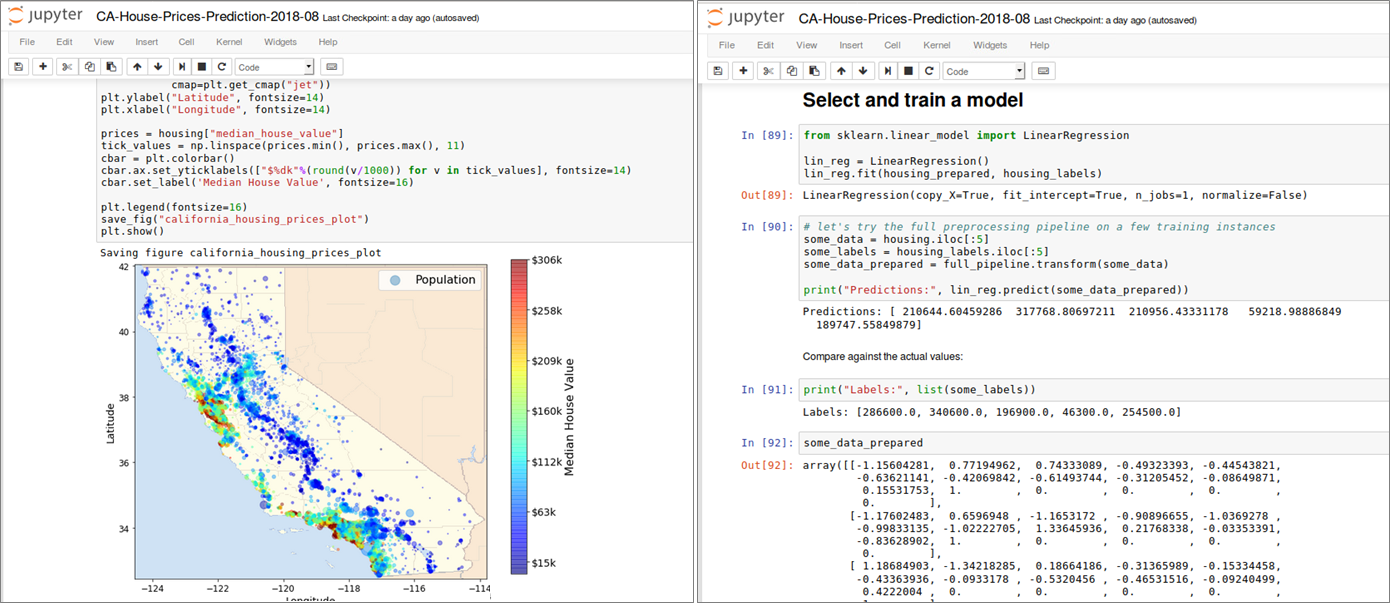

Ein Problem, auf das man bei der praktischen Arbeit mit lokalen Jupyter-Installationen schnell stößt, lässt sich mit dem “works on my machine”-Syndrom bezeichnen. Kleine Data Sets funktionieren problemlos auf einem lokalen Rechner, wenn sie aber auf die Größe des Produktionsdatenbestandes migriert werden, skaliert das Einlesen und Verarbeiten aller Daten mit einem einzelnen Rechner nicht. Aufgrund dieser Begrenzung liegt der Aufbau einer server-basierten ML-Umgebung mit ausreichend Rechen- und Speicherkapazität auf der Hand. Dabei ist aber die Einrichtung einer solchen ML-Umgebung, insbesondere bei einer on-premise Infrastruktur, eine Herausforderung: Das Infrastruktur-Team muss physische Server und/oder virtuelle Maschinen (VM’s) auf Anforderung bereitstellen und integrieren. Dieser Ansatz ist aufgrund vieler manueller Arbeitsschritte zeitaufwändig und fehleranfällig. Mit dem Einsatz Cloud-basierter Technologien vereinfacht sich dieser Prozess deutlich. Die Möglichkeit, Infrastructure on Demand zu verwenden und z.B. mit einem skalierbaren Cloud-Data Warehouse zu kombinieren, bietet sofortigen Zugriff auf Rechen- und Speicher-Ressourcen, wann immer sie benötigt werden und reduziert den administrativen Aufwand bei Einrichtung und Verwaltung der zum Einsatz kommenden ML-Software. Bild 5 zeigt den Code-Ausschnitt aus einem Jupyter Notebook, das im Rahmen des Cloud Services Amazon SageMaker bereitgestellt wird und via PySpark Kernel auf einen Multi-Node Apache Spark Cluster (in einer Amazon EMR-Umgebung) zugreift. In diesem Szenario wird aus einem Snowflake Cloud Data Warehouse ein größeres Data Set mit 220 Millionen Datensätzen via Spark-Connector komplett in ein Spark Dataframe geladen und im Spark Cluster weiterverarbeitet. Den vollständigen Prozess inkl. Einrichtung und Konfiguration aller Komponenten, beschreibt eine vierteilige Blog-Serie [8]). Mit Spark Cluster sowie Snowflake stehen für sich genommen zwei leistungsfähige Umgebungen für rechenintensive Aufgaben zur Verfügung. Mit dem aktuellen Snowflake Connector für Spark ist eine intelligente Arbeitsteilung mittels Query Pushdown erreichbar. Dabei entscheidet Spark’s optimizer (Catalyst), welche Aufgaben (Queries) aufgrund der effizienteren Verarbeitung an Snowflake delegiert werden [9].

Abbildung 5: Jupyter Notebook in der Cloud – integriert mit Multi-Node Spark Cluster und Snowflake Cloud Data Warehouse

Welches Machine Learning Framework für welche Aufgabenstellung?

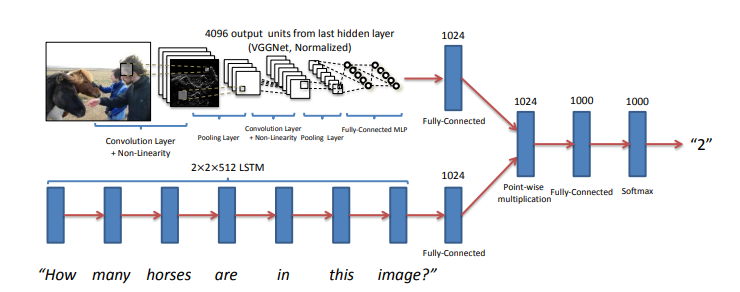

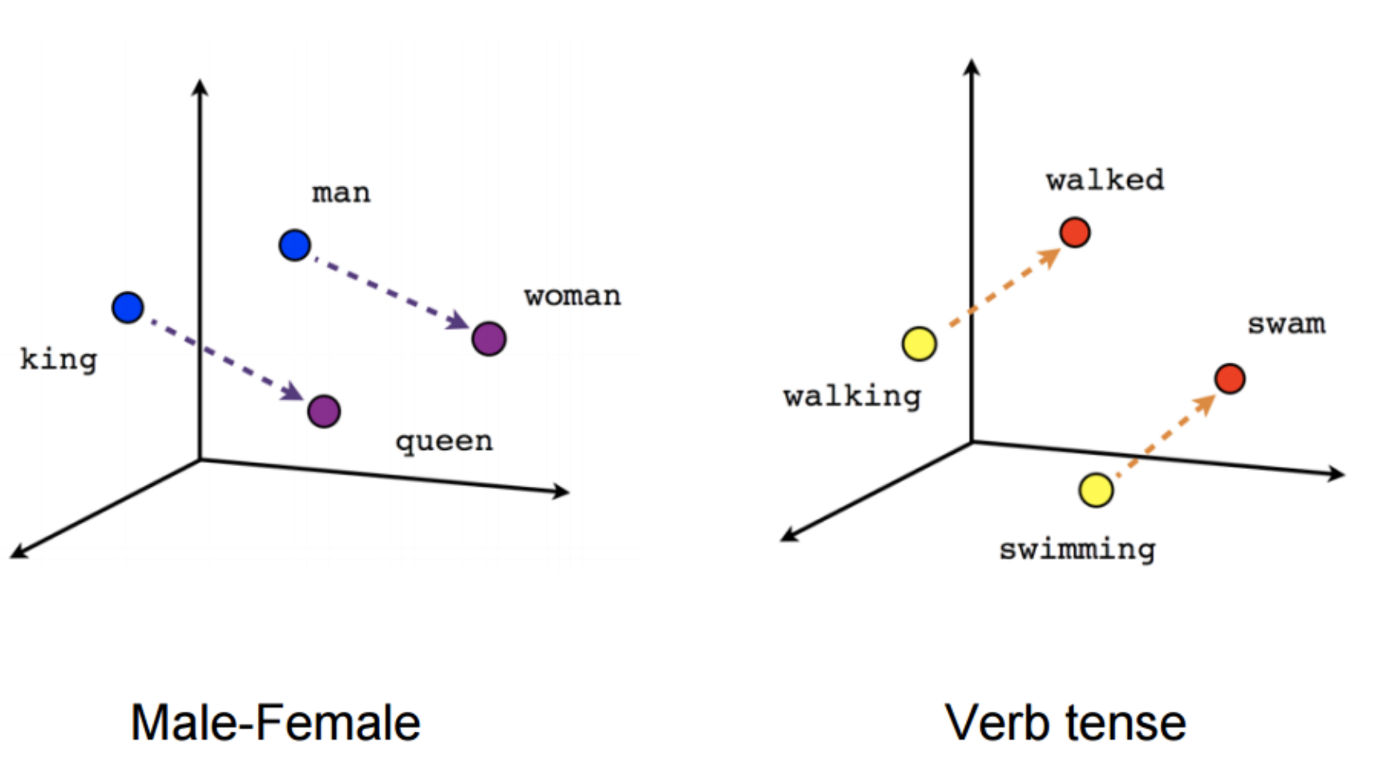

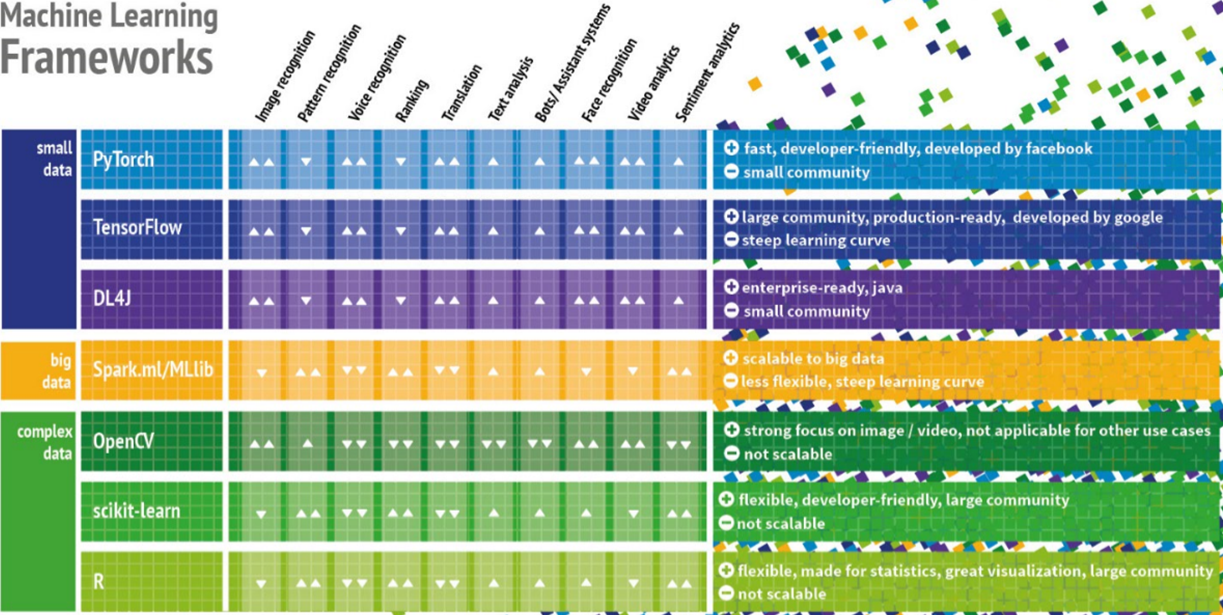

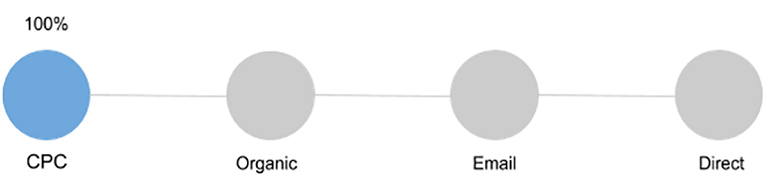

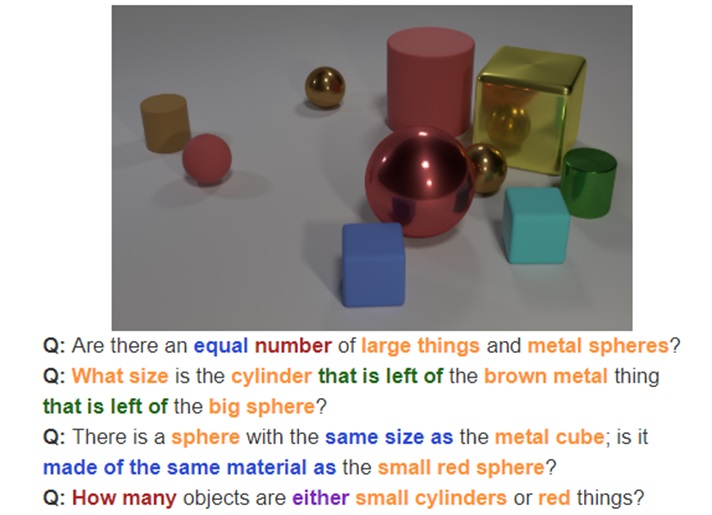

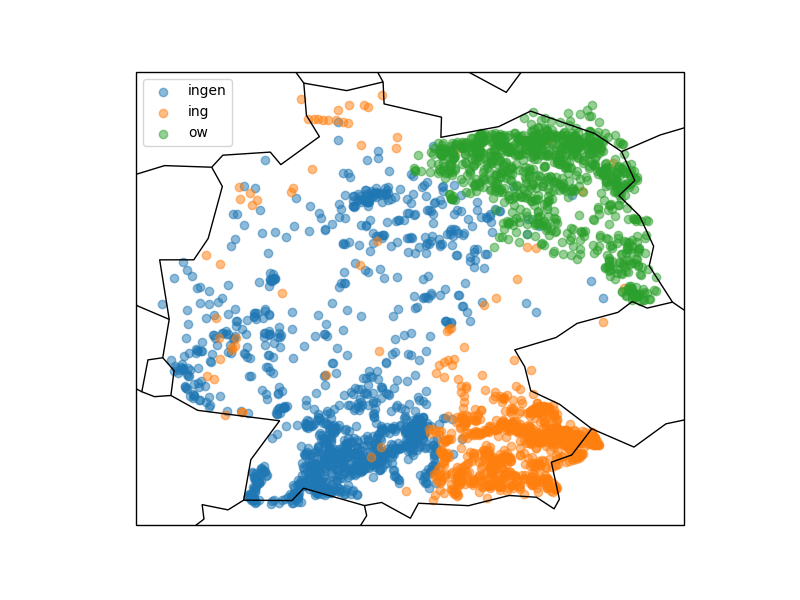

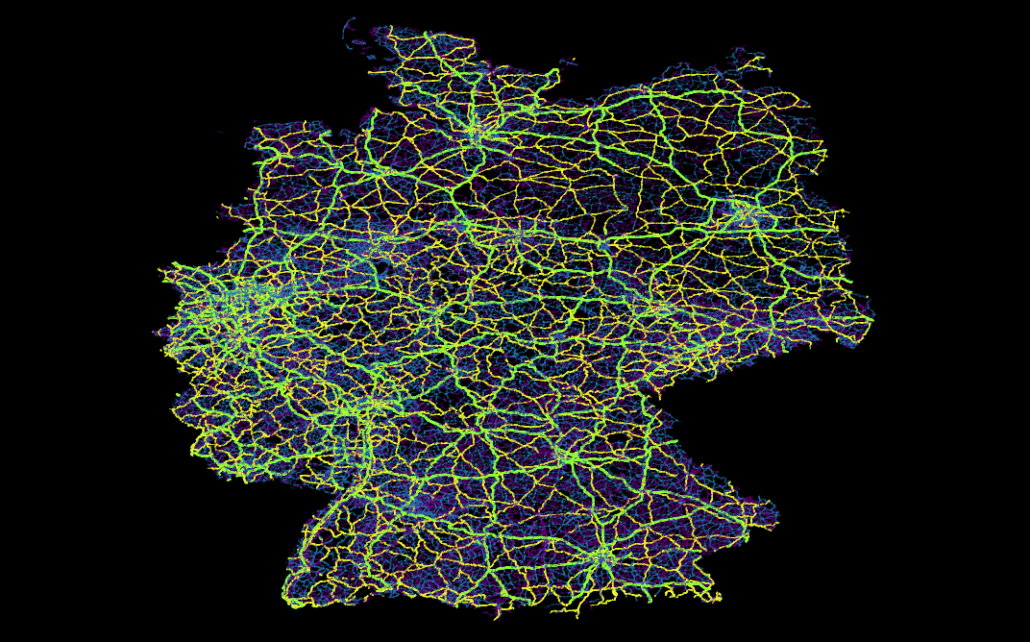

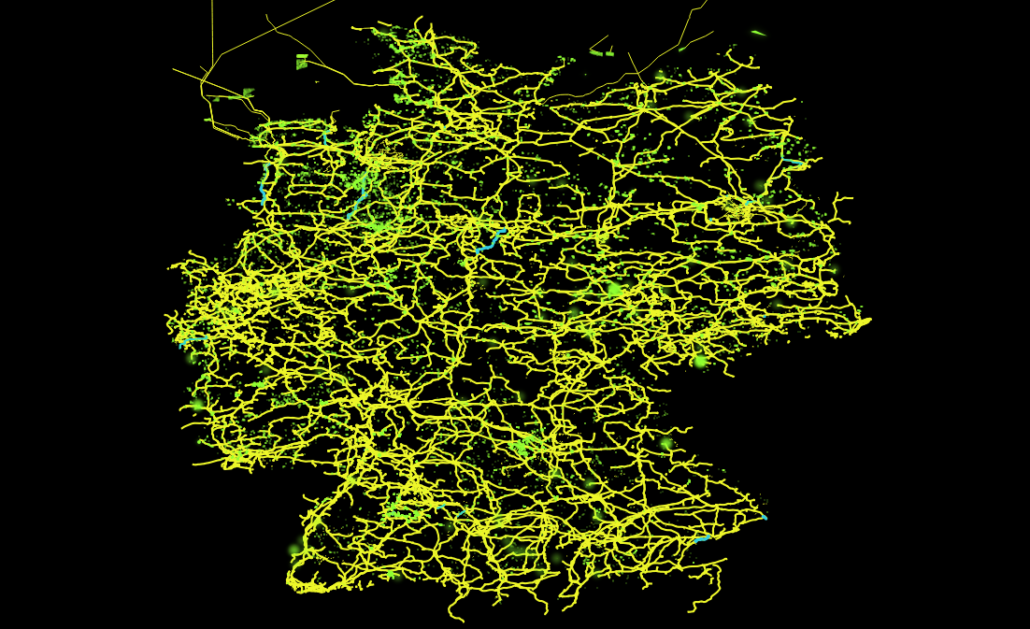

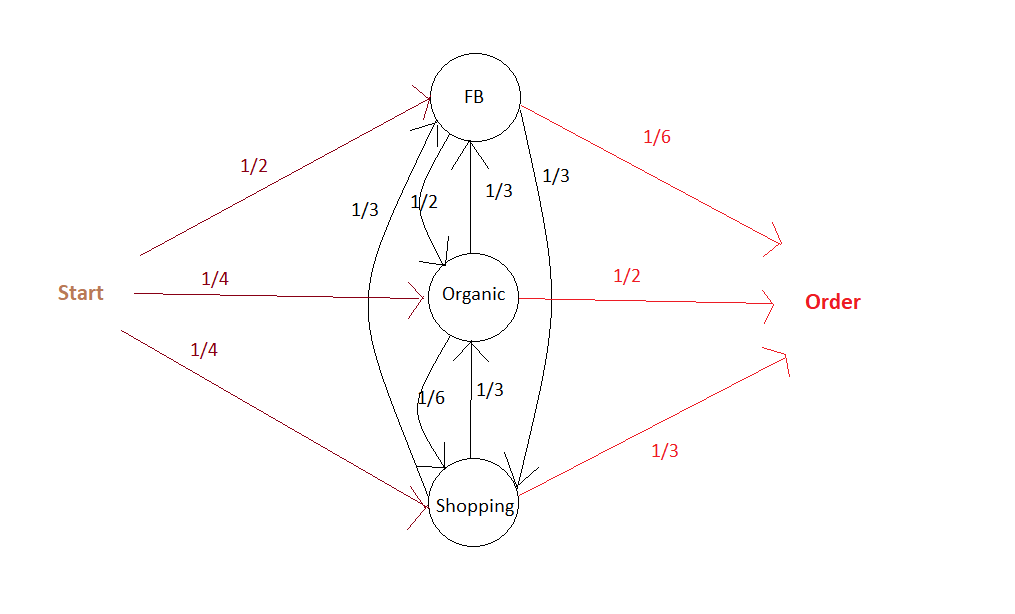

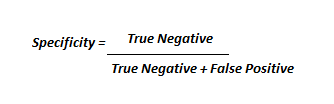

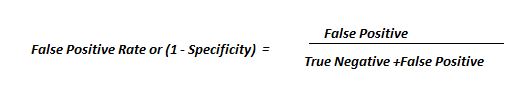

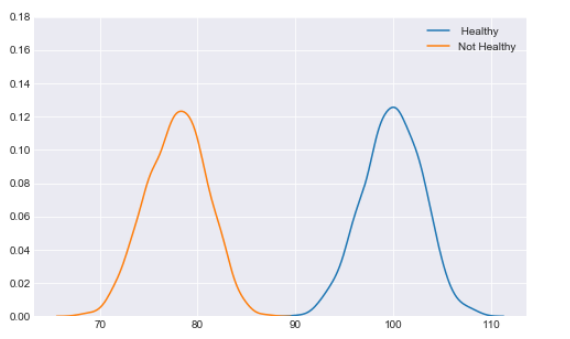

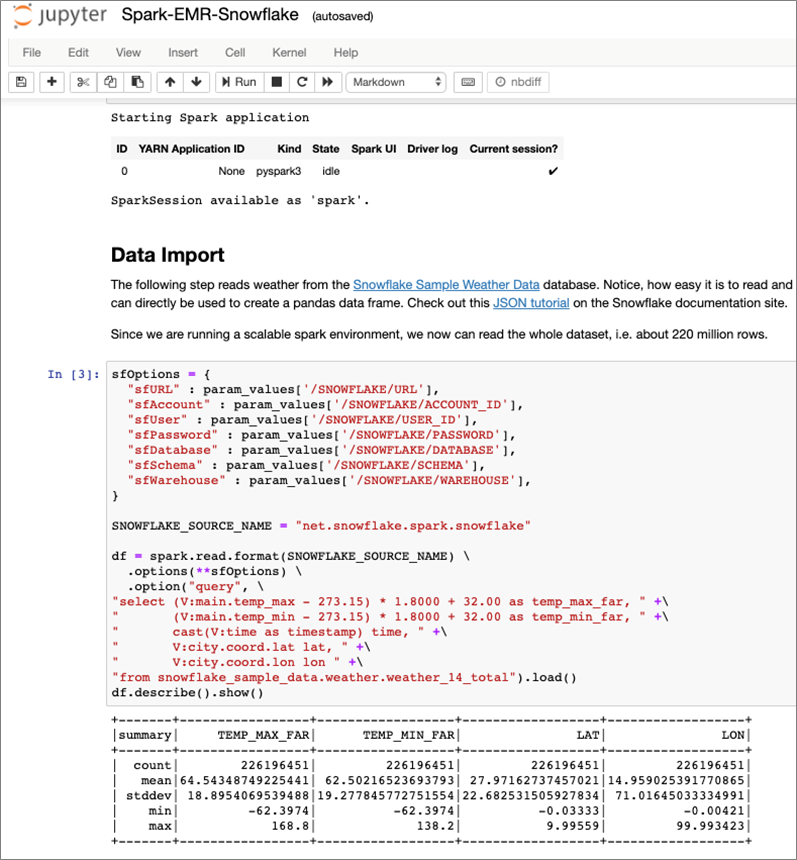

Bevor die nächsten Abschnitte weitere Werkzeuge und Technologien betrachten, macht es nicht nur für Data Scientists sondern auch für IT-Architekten Sinn, zunächst einen Überblick auf die derzeit verfügbaren Machine Learning Frameworks zu bekommen. Aus Architekturperspektive ist es wichtig zu verstehen, welche Aufgabenstellungen die jeweiligen ML-Frameworks adressieren, welche technischen Anforderungen und ggf. auch Abhängigkeiten zu den verfügbaren Datenquellen bestehen. Ein gemeinsamer Nenner vieler gescheiterter Machine Learning-Projekte ist häufig die Auswahl des falschen Frameworks. Ein Beispiel: TensorFlow ist aktuell eines der wichtigsten Frameworks zur Programmierung von neuronalen Netzen, Deep Learning Modellen sowie anderer Machine Learning Algorithmen. Während Deep Learning perfekt zur Untersuchung komplexer Daten wie Bild- und Audiodaten passt, wird es zunehmend auch für Use Cases benutzt, für die andere Frameworks besser geeignet sind. Bild 6 zeigt eine kompakte Entscheidungsmatrix [10] für die derzeit verbreitetsten ML-Frameworks und adressiert häufige Praxisprobleme: Entweder werden Algorithmen benutzt, die für den Use Case nicht oder kaum geeignet sind oder das gewählte Framework kann die aufkommenden Datenmengen nicht bewältigen. Die Unterteilung der Frameworks in Small Data, Big Data und Complex Data ist etwas plakativ, soll aber bei der Auswahl der Frameworks nach Art und Volumen der Daten helfen. Die Grenze zwischen Big Data zu Small Data ist dabei dort zu ziehen, wo die Datenmengen so groß sind, dass sie nicht mehr auf einem einzelnen Computer, sondern in einem verteilten Cluster ausgewertet werden müssen. Complex Data steht in dieser Matrix für unstrukturierte Daten wie Bild- und Audiodateien, für die sich Deep Learning Frameworks sehr gut eignen.

Abbildung 6: Entscheidungsmatrix zu aktuell verbreiteten Machine Learning Frameworks

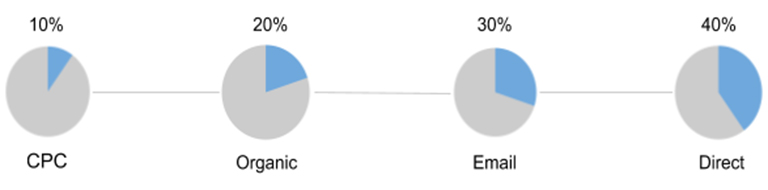

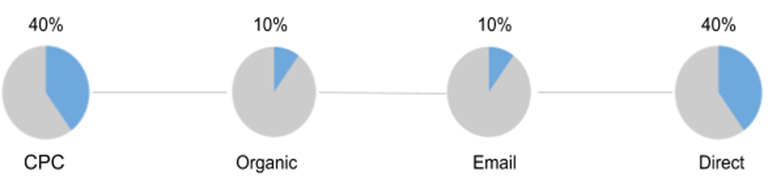

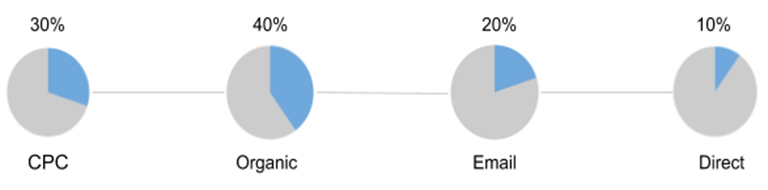

Self-Service Machine Learning in Business Intelligence-Tools

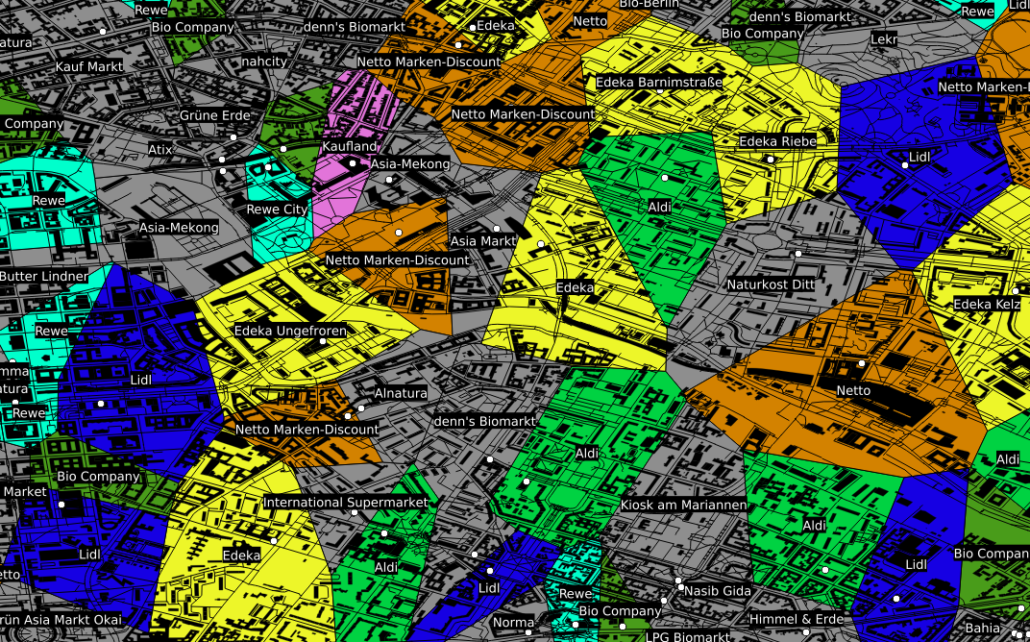

Mit einfach zu bedienenden Business Intelligence-Werkzeugen zur Datenvisualisierung ist es für Analytiker und für weniger technisch versierte Anwender recht einfach, komplexe Daten aussagekräftig in interaktiven Dashboards zu präsentieren. Hersteller wie Tableau, Qlik und Oracle spielen ihre Stärken insbesondere im Bereich Visual Analytics aus. Statt statische Berichte oder Excel-Dateien vor dem nächsten Meeting zu verschicken, erlauben moderne Besprechungs- und Kreativräume interaktive Datenanalysen am Smartboard inklusive Änderung der Abfragefilter, Perspektivwechsel und Drill-downs. Im Rahmen von Data Science-Projekten können diese Werkzeuge sowohl zur Exploration von Daten als auch zur Visualisierung der Ergebnisse komplexer Machine Learning-Modelle sinnvoll eingesetzt werden. Prognosen, Scores und weiterer ML-Modell-Output lässt sich so schneller verstehen und unterstützt die Entscheidungsfindung bzw. Ableitung der nächsten Maßnahmen für den Geschäftsprozess. Im Rahmen einer IT-Gesamtarchitektur sind Analyse-Notebooks und Datenvisualisierungswerkzeuge für die Standard-Analytics-Toolbox Unternehmens gesetzt. Mit Hinblick auf effiziente Team-Zusammenarbeit, unternehmensinternen Austausch und Kommunikation von Ergebnissen sollte aber nicht nur auf reine Desktop-Werkzeuge gesetzt, sondern Server-Lösungen betrachtet und zusammen mit einem Nutzerkonzept eingeführt werden, um zehnfache Report-Dubletten, konkurrierende Statistiken („MS Excel Hell“) einzudämmen.

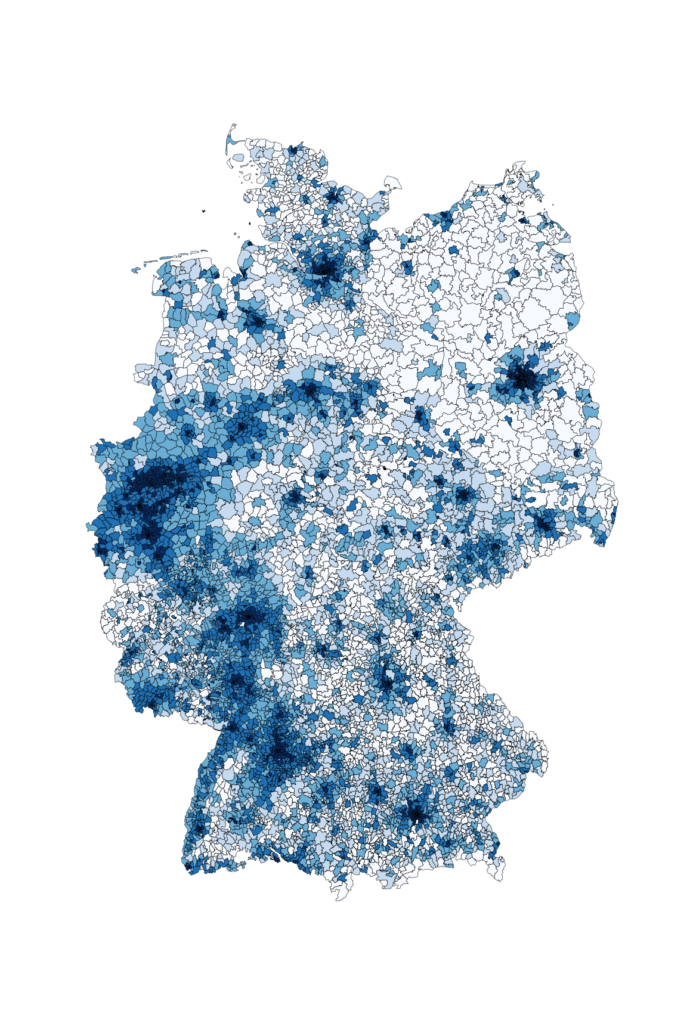

Abbildung 7: Datenexploration in Tableau – leicht gemacht für Fachanwender und Data Scientists

Zusätzliche Statistikfunktionen bis hin zur Möglichkeit R- und Python-Code bei der Analyse auszuführen, öffnet auch Fachanwender die Tür zur Welt des Maschinellen Lernens. Bild 7 zeigt das Werkzeug Tableau Desktop mit der Analyse kalifornischer Hauspreise (demselben Datensatz wie oben im Jupyter Notebook-Abschnitt wie in Bild 4) und einer Heatmap-Visualisierung zur Hervorhebung der teuersten Wohnlagen. Mit wenigen Klicks ist auch der Einsatz deskriptiver Statistik möglich, mit der sich neben Lagemaßen (Median, Quartilswerte) auch Streuungsmaße (Spannweite, Interquartilsabstand) sowie die Form der Verteilung direkt aus dem Box-Plot in Bild 7 ablesen und sogar über das Vorhandensein von Ausreißern im Datensatz eine Feststellung treffen lassen. Vorteil dieser Visualisierungen sind ihre hohe Informationsdichte, die allerdings vom Anwender auch richtig interpretiert werden muss. Bei der Beurteilung der Attribute, mit ihren Wertausprägungen und Abhängigkeiten innerhalb des Data Sets, benötigen Citizen Data Scientists (eine Wortschöpfung von Gartner) allerdings dann doch die mathematischen bzw. statistischen Grundlagen, um Falschinterpretationen zu vermeiden. Fraglich ist auch der Nutzen des Data Flow Editors [11] in Oracle Data Visualization, mit dem eins oder mehrere der im Werkzeug integrierten Machine Learning-Modelle trainiert und evaluiert werden können: technisch lassen sich Ergebnisse erzielen und anhand einiger Performance-Metriken die Modellgüte auch bewerten bzw. mit anderen Modellen vergleichen – aber wer kann die erzielten Ergebnisse (wissenschaftlich) verteidigen? Gleiches gilt für die Integration vorhandener R- und Python Skripte, die am Ende dann doch eine Einweisung der Anwender bzgl. Parametrisierung der ML-Modelle und Interpretationshilfen bei den erzielten Ergebnissen erfordern.

Machine Learning in und mit Datenbanken

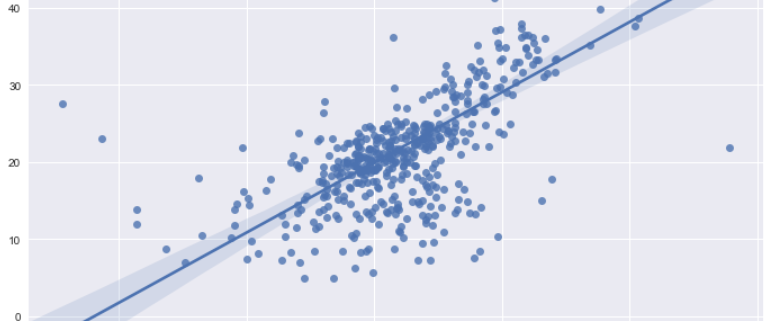

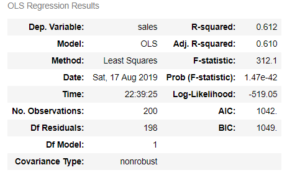

Die Nutzung eingebetteter 1-click Analytics-Funktionen der oben vorgestellten Data Visualization-Tools ist zweifellos komfortabel und zum schnellen Experimentieren geeignet. Der gegenteilige und eher puristische Ansatz wäre dagegen die Implementierung eigener Machine Learning Modelle in der Datenbank. Für die Umsetzung des gewählten Algorithmus reichen schon vorhandene Bordmittel in der Datenbank aus: SQL inklusive mathematischer und statistische SQL-Funktionen, Tabellen zum Speichern der Ergebnisse bzw. für das ML-Modell-Management und Stored Procedures zur Abbildung komplexer Geschäftslogik und auch zur Ablaufsteuerung. Solange die Algorithmen ausreichend skalierbar sind, gibt es viele gute Gründe, Ihre Data Warehouse Engine für ML einzusetzen:

- Einfachheit – es besteht keine Notwendigkeit, eine andere Compute-Plattform zu managen, zwischen Systemen zu integrieren und Daten zu extrahieren, transferieren, laden, analysieren usw.

- Sicherheit – Die Daten bleiben dort, wo sie gut geschützt sind. Es ist nicht notwendig, Datenbank-Anmeldeinformationen in externen Systemen zu konfigurieren oder sich Gedanken darüber zu machen, wo Datenkopien verteilt sein könnten.

- Performance – Eine gute Data Warehouse Engine verwaltet zur Optimierung von SQL Abfragen viele Metadaten, die auch während des ML-Prozesses wiederverwendet werden könnten – ein Vorteil gegenüber General-purpose Compute Plattformen.

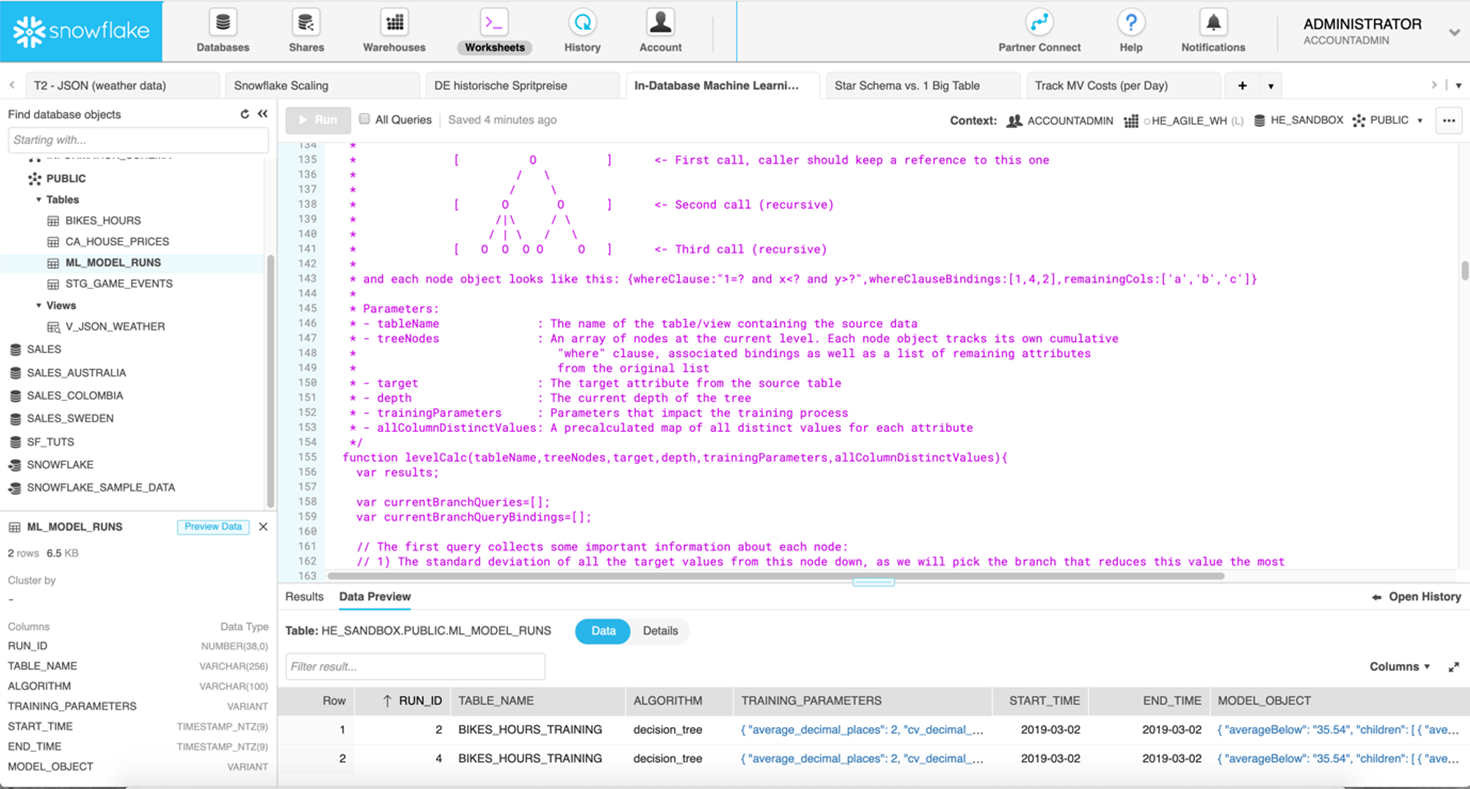

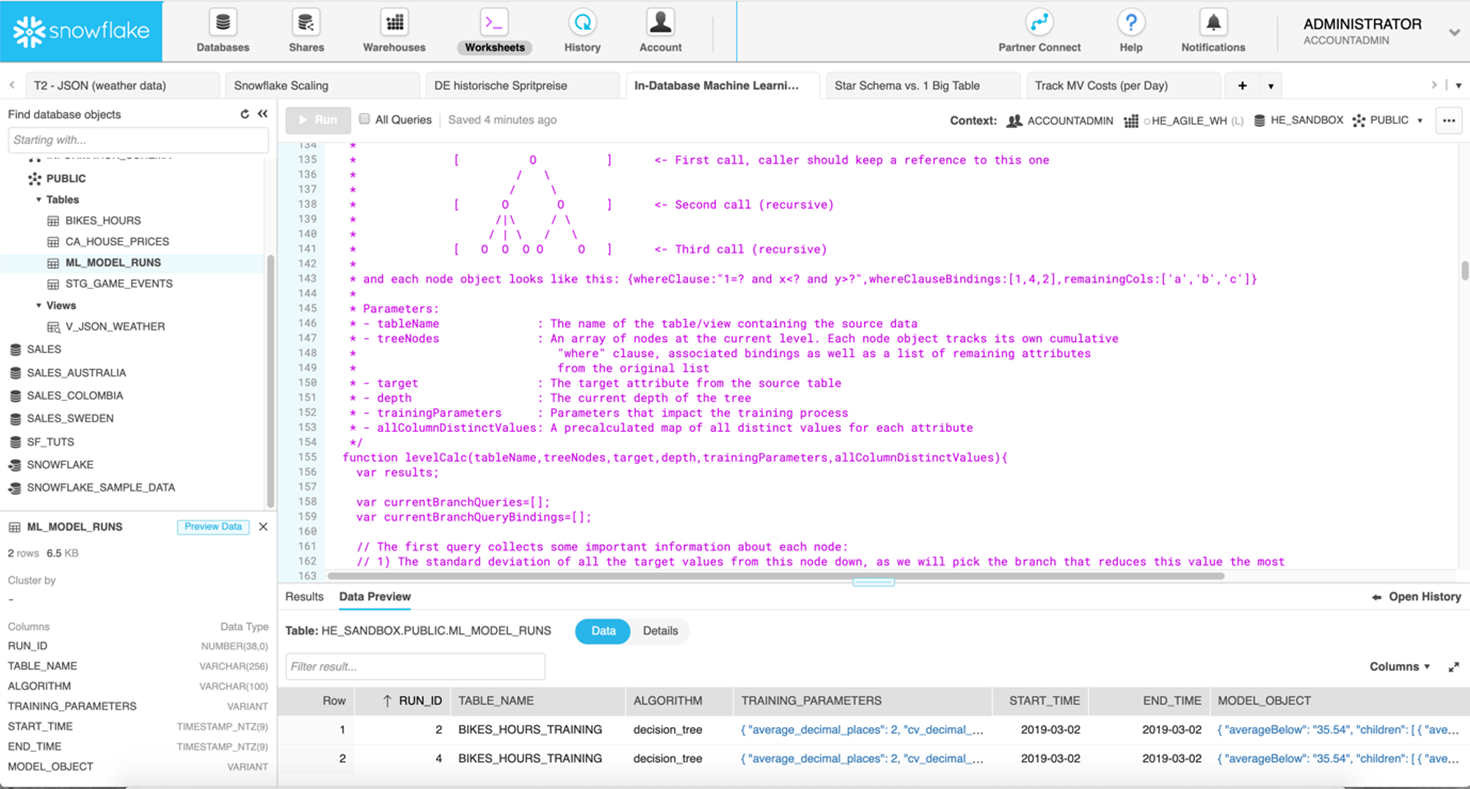

Die Implementierung eines minimalen, aber legitimen ML-Algorithmus wird in [12] am Beispiel eines Entscheidungsbaums (Decision Tree) im Snowflake Data Warehouse gezeigt. Decision Trees kommen für den Aufbau von Regressions- oder Klassifikationsmodellen zum Einsatz, dabei teilt man einen Datensatz in immer kleinere Teilmengen auf, die ihrerseits in einem Baum organisiert sind. Bild 8 zeigt die Snowflake Benutzeroberfläche und ein Ausschnitt von der Stored Procedure, die dynamisch alle SQL-Anweisungen zur Berechnung des Decision Trees nach dem ID3 Algorithmus [13] generiert.

Abbildung 8: Snowflake SQL-Editor mit Stored Procedure zur Berechnung eines Decission Trees

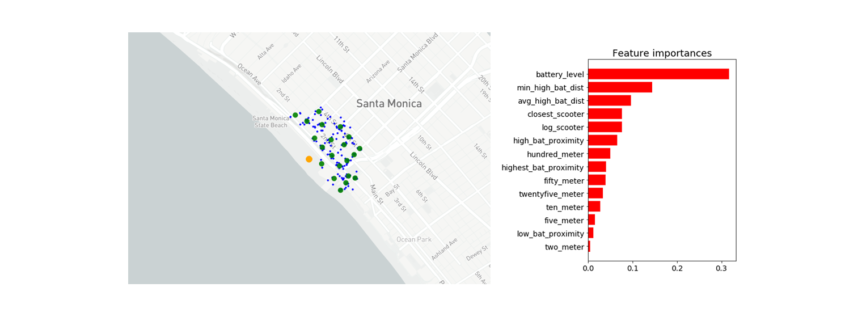

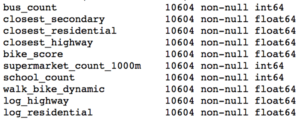

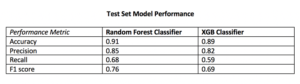

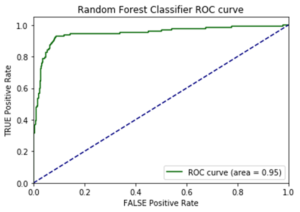

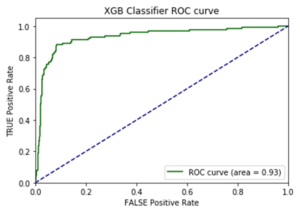

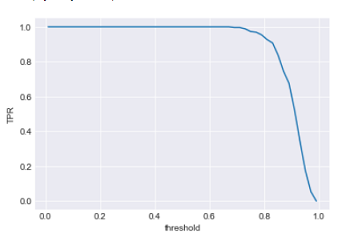

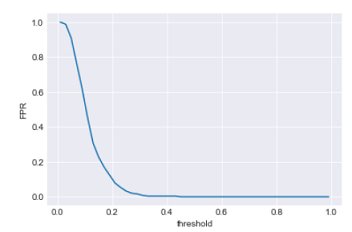

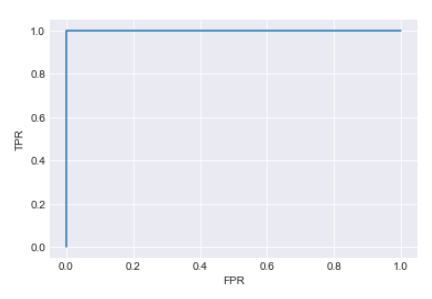

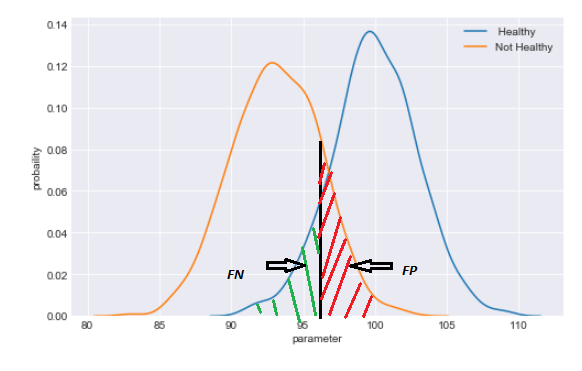

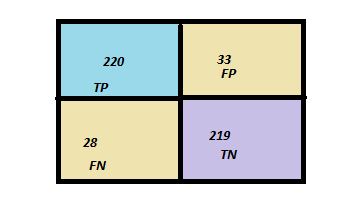

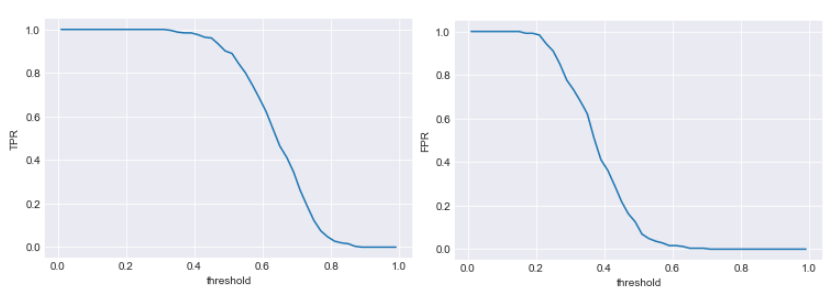

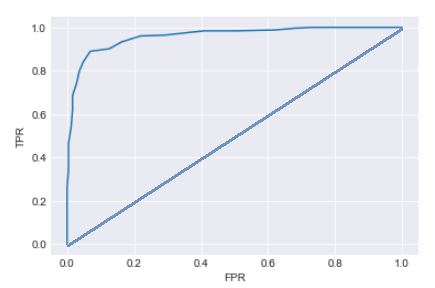

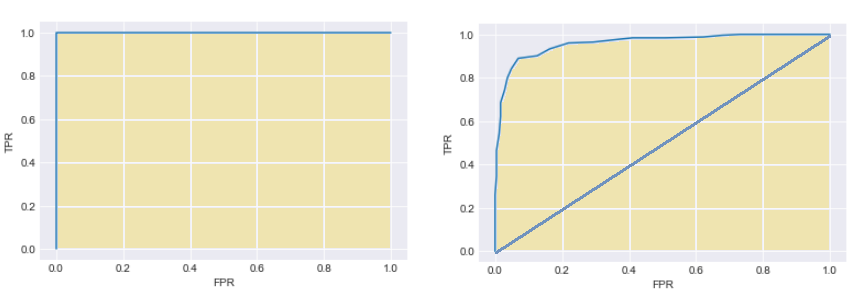

Allerdings ist der Entwicklungs- und Implementierungsprozess für ein Machine Learning Modell umfassender: Es sind relevante Daten zu identifizieren und für das ML-Modell vorzubereiten. Einfach Rohdaten bzw. nicht aggregierten Informationen aus Datenbanktabellen zu extrahieren reicht nicht aus, stattdessen benötigt ein ML-Modell als Input eine flache, meist sehr breite Tabelle mit vielen Aggregaten, die als Features bezeichnet werden. Erst dann kann der Prozess fortgesetzt und der für die Aufgabenstellung ausgewählte Algorithmus trainiert und die Modellgüte bewertet werden. Ist das Ergebnis zufriedenstellend, steht die Implementierung des ML-Modells in der Zielumgebung an und muss sich künftig beim Scoring „frischer Datensätze“ bewähren. Viele zeitaufwändige Teilaufgaben also, bei der zumindest eine Teilautomatisierung wünschenswert wäre. Allein die Datenaufbereitung kann schon bis zu 70…80% der gesamten Projektzeit beanspruchen. Und auch die Implementierung eines ML-Modells wird häufig unterschätzt, da in Produktionsumgebungen der unterstützte Technologie-Stack definiert und ggf. für Machine Learning-Aufgaben erweitert werden muss. Daher ist es reizvoll, wenn das Datenbankmanagement-System auch hier einsetzbar ist – sofern die geforderten Algorithmen dort abbildbar sind. Wie ein ML-Modell für die Kundenabwanderungsprognose (Churn Prediction) werkzeuggestützt mit Xpanse AI entwickelt und beschleunigt im Snowflake Cloud Data Warehouse bereitgestellt werden kann, beschreibt [14] sehr anschaulich: Die benötigten Datenextrakte sind schnell aus Snowflake entladen und stellen den Input für ein neues Xpanse AI-Projekt dar. Sobald notwendige Tabellenverknüpfungen und andere fachliche Informationen hinterlegt sind, analysiert das Tool Datenstrukturen und transformiert alle Eingangstabellen in eine flache Zwischentabelle (u.U. mit Hunderten von Spalten), auf deren Basis im Anschluss ML-Modelle trainiert werden. Nach dem ML-Modell-Training erfolgt die Begutachtung der Ergebnisse: das erstellte Dataset, Güte des ML-Modells und der generierte SQL(!) ETL-Code zur Erstellung der Zwischentabelle sowie die SQL-Repräsentation des ML-Modells, das basierend auf den Input-Daten Wahrscheinlichkeitswerte berechnet und in einer Scoring-Tabelle ablegt. Die Vorteile dieses Ansatzes sind liegen auf der Hand: kürzere Projektzeiten, der Einsatz im Rahmen des Snowflake Cloud Data Warehouse, macht das Experimentieren mit der Zuweisung dedizierter Compute-Ressourcen für die performante Verarbeitung äußerst einfach. Grenzen liegen wiederum bei der zur Verfügung stehenden Algorithmen.

Spezialisierte Software Suites für Machine Learning

Während sich im Markt etablierte Business Intelligence- und Datenintegrationswerkzeuge mit Erweiterungen zur Ausführung von Python- und R-Code als notwendigen Bestandteil der Analyse-Toolbox für den Data Science Prozess positionieren, gibt es daneben auch Machine-Learning-Plattformen, die auf die Arbeit mit künstlicher Intelligenz (KI) zugeschnittenen sind. Für den Einstieg in Data Science bieten sich die oft vorhandenen quelloffenen Distributionen an, die auch über Enterprise-Versionen mit erweiterten Möglichkeiten für beschleunigtes maschinelles Lernen durch Einsatz von Grafikprozessoren (GPUs), bessere Skalierung sowie Funktionen für das ML-Modell Management (z.B. durch Versionsmanagement und Automatisierung) verfügen.

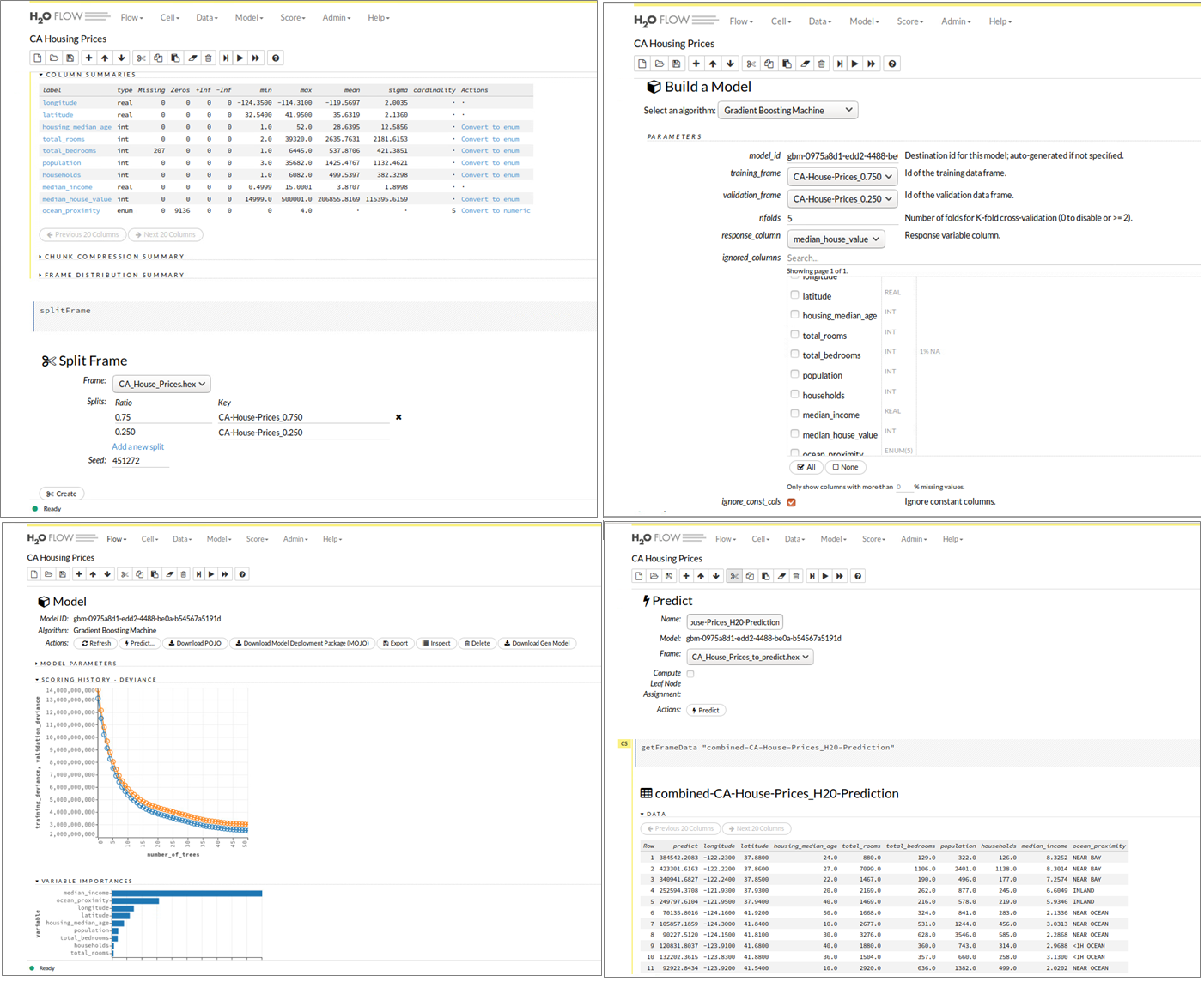

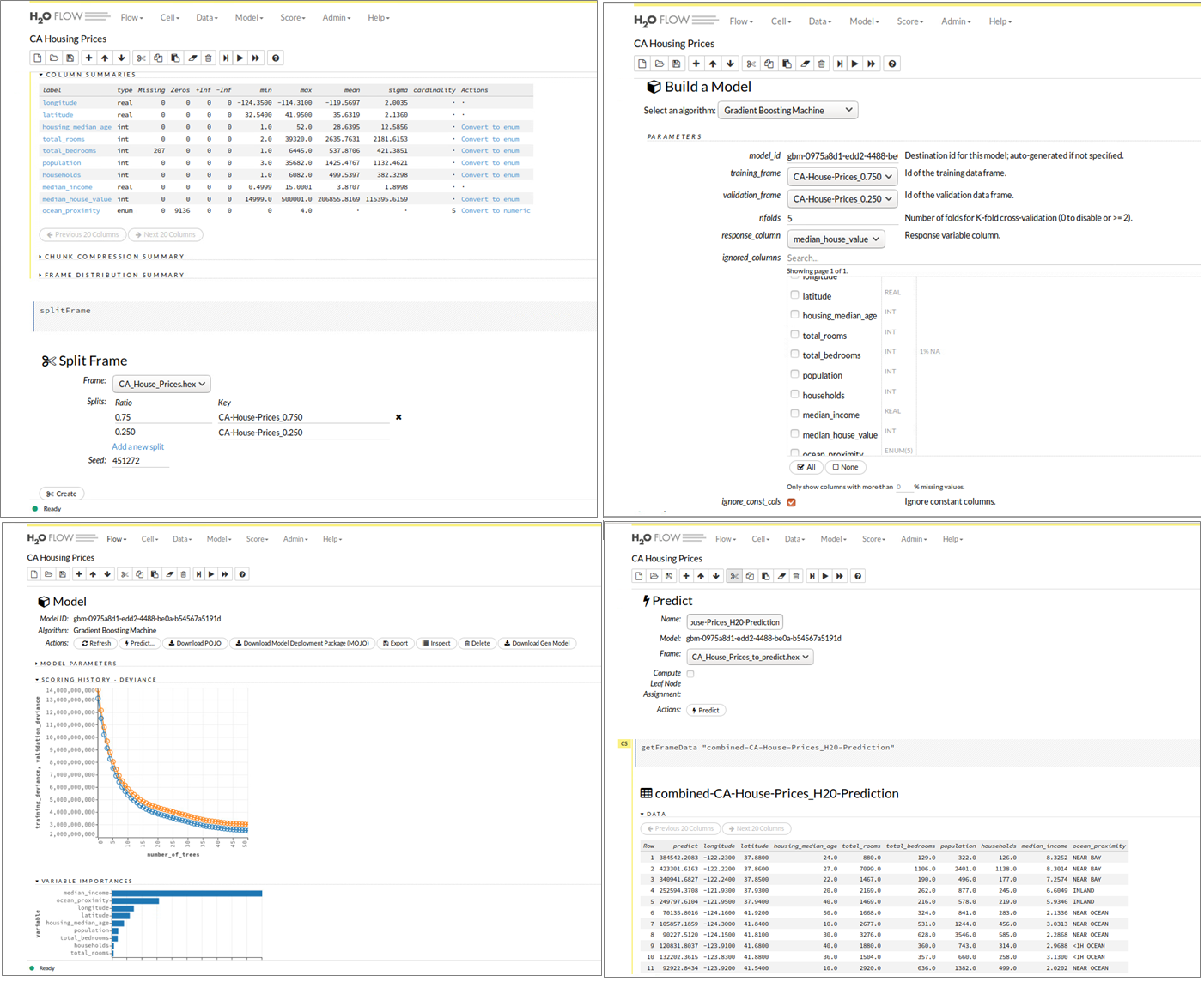

Eine beliebte Machine Learning-Suite ist das Open Source Projekt H2O. Die Lösung des gleichnamigen kalifornischen Unternehmens verfügt über eine R-Schnittstelle und ermöglicht Anwendern dieser statistischen Programmiersprache Vorteile in puncto Performance. Die in H2O verfügbaren Funktionen und Algorithmen sind optimiert und damit eine gute Alternative für das bereits standardmäßig in den R-Paketen verfügbare Funktionsset. H2O implementiert Algorithmen aus dem Bereich Statistik, Data-Mining und Machine Learning (generalisierte Lineare Modelle, K-Means, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting und Deep Learning) und bietet mit einer In-Memory-Architektur und durch standardmäßige Parallelisierung über alle vorhandenen Prozessorkerne eine gute Basis, um komplexe Machine-Learning-Modelle schneller trainieren zu können. Bild 9 zeigt wieder anhand des Datensatzes zur Analyse der kalifornischen Hauspreise die webbasierte Benutzeroberfläche H20 Flow, die den oben beschriebenen Juypter Notebook-Ansatz mit zusätzlich integrierter Benutzerführung für die wichtigsten Prozessschritte eines Machine-Learning-Projektes kombiniert. Mit einigen Klicks kann das California Housing Dataset importiert, in einen H2O-spezifischen Dataframe umgewandelt und anschließend in Trainings- und Testdatensets aufgeteilt werden. Auswahl, Konfiguration und Training der Machine Learning-Modelle erfolgt entweder durch den Anwender im Einsteiger-, Fortgeschrittenen- oder Expertenmodus bzw. im Auto-ML-Modus. Daran anschließend erlaubt H20 Flow die Vorhersage für die Zielvariable (im Beispiel: Hauspreis) für noch unbekannte Datensätze und die Aufbereitung der Ergebnismenge. Welche Unterstützung H2O zur Produktivsetzung von ML-Modellen anbietet, wird an einem Beispiel in den folgenden Abschnitten betrachtet.

Abbildung 9: H2O Flow Benutzeroberfläche – Datenaufbereitung, ML-Modell-Training und Evaluierung.

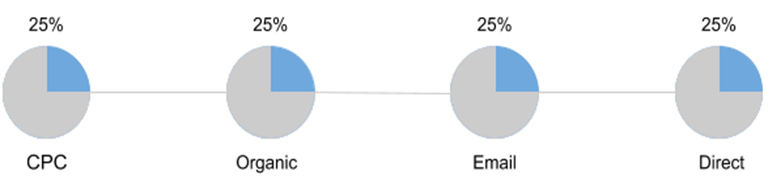

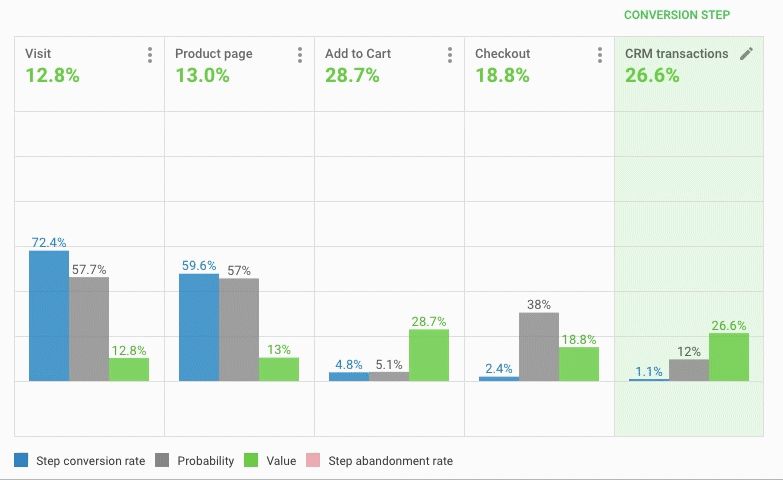

Vom Prototyp zur produktiven Machine Learning-Lösung

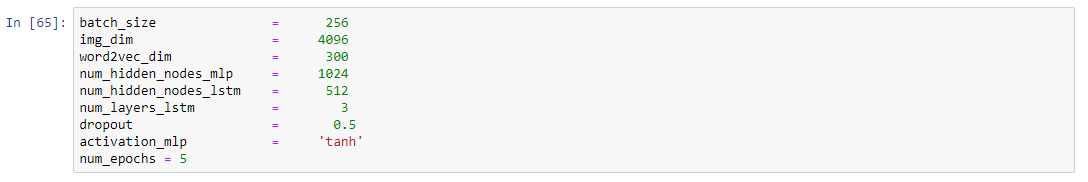

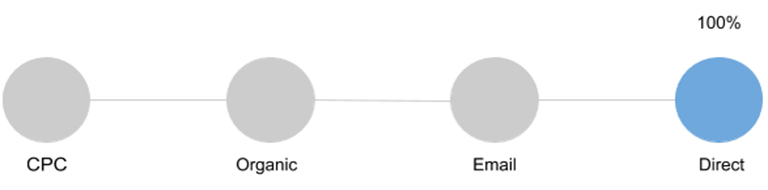

Warum ist es für viele Unternehmen noch schwer, einen Nutzen aus ihren ersten Data Science-Aktivitäten, Data Labs etc. zu ziehen? In der Praxis zeigt sich, erst durch Operationalisierung von Machine Learning-Resultaten in der Produktionsumgebung entsteht echter Geschäftswert und nur im Tagesgeschäft helfen robuste ML-Modelle mit hoher Güte bei der Erreichung der gesteckten Unternehmensziele. Doch leider erweist sich der Weg vom Prototypen bis hin zum Produktiveinsatz bei vielen Initativen noch als schwierig. Bild 10 veranschaulicht ein typisches Szenario: Data Science-Teams fällt es in ihrer Data Lab-Umgebung technisch noch leicht, Prototypen leistungsstarker ML-Modelle mit Hilfe aktueller ML-Frameworks wie TensorFlow-, Keras- und Word2Vec auf ihren Laptops oder in einer Sandbox-Umgebung zu erstellen. Doch je nach verfügbarer Infrastruktur kann, wegen Begrenzungen bei Rechenleistung oder Hauptspeicher, nur ein Subset der Produktionsdaten zum Trainieren von ML-Modellen herangezogen werden. Ergebnispräsentationen an die Stakeholder der Data Science-Projekte erfolgen dann eher durch Storytelling in MS Powerpoint bzw. anhand eines Demonstrators – selten aber technisch schon so umgesetzt, dass anderere Applikationen z.B. über eine REST-API von dem neuen Risiko Scoring-, dem Bildanalyse-Modul etc. (testweise) Gebrauch machen können. Ausgestattet mit einer Genehmigung vom Management, übergibt das Data Science-Team ein (trainiertes) ML-Modell an das Software Engineering-Team. Nach der Übergabe muss sich allerdings das Engineering-Team darum kümmern, dass das ML-Modell in eine für den Produktionsbetrieb akzeptierte Programmiersprache, z.B. in Java, neu implementiert werden muss, um dem IT-Unternehmensstandard (siehe Line of Governance in Bild 10) bzw. Anforderungen an Skalierbarkeit und Laufzeitverhalten zu genügen. Manchmal sind bei einem solchen Extraschritt Abweichungen beim ML-Modell-Output und in jedem Fall signifikante Zeitverluste beim Deployment zu befürchten.

Abbildung 10: Übergabe von Machine Learning-Resultaten zur Produktivsetzung im Echtbetrieb

Unterstützt das Data Science-Team aktiv bei dem Deployment, dann wäre die Einbettung des neu entwickelten ML-Modells in eine Web-Applikation eine beliebte Variante, bei der typischerweise Flask, Tornado (beides Micro-Frameworks für Python) und Shiny (ein auf R basierendes HTML5/CSS/JavaScript Framework) als Technologiekomponenten zum Zuge kommen. Bei diesem Vorgehen müssen ML-Modell, Daten und verwendete ML-Pakete/Abhängigkeiten in einem Format verpackt werden, das sowohl in der Data Science Sandbox als auch auf Produktionsservern lauffähig ist. Für große Unternehmen kann dies einen langwierigen, komplexen Softwareauslieferungsprozess bedeuten, der ggf. erst noch zu etablieren ist. In dem Zusammenhang stellt sich die Frage, wie weit die Erfahrung des Data Science-Teams bei der Entwicklung von Webanwendungen reicht und Aspekte wie Loadbalancing und Netzwerkverkehr ausreichend berücksichtigt? Container-Virtualisierung, z.B. mit Docker, zur Isolierung einzelner Anwendungen und elastische Cloud-Lösungen, die on-Demand benötigte Rechenleistung bereitstellen, können hier Abhilfe schaffen und Teil der Lösungsarchitektur sein. Je nach analytischer Aufgabenstellung ist das passende technische Design [15] zu wählen: Soll das ML-Modell im Batch- oder Near Realtime-Modus arbeiten? Ist ein Caching für wiederkehrende Modell-Anfragen vorzusehen? Wie wird das Modell-Deployment umgesetzt, In-Memory, Code-unabhängig durch Austauschformate wie PMML, serialisiert via R- oder Python-Objekte (Pickle) oder durch generierten Code? Zusätzlich muss für den Produktiveinsatz von ML-Modellen auch an unterstützenden Konzepten zur Bereitstellung, Routing, Versionsmanagement und Betrieb im industriellen Maßstab gearbeitet werden, damit zuverlässige Machine Learning-Produkte bzw. -Services zur internen und externen Nutzung entstehen können (siehe dazu Bild 11)

Abbildung 11: Unterstützende Funktionen für produktive Machine Learning-Lösungen

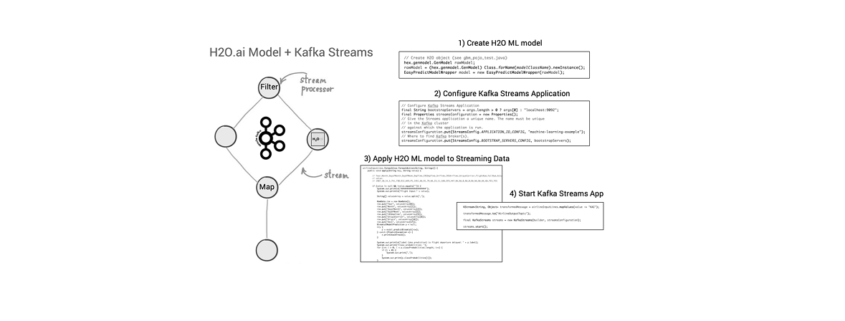

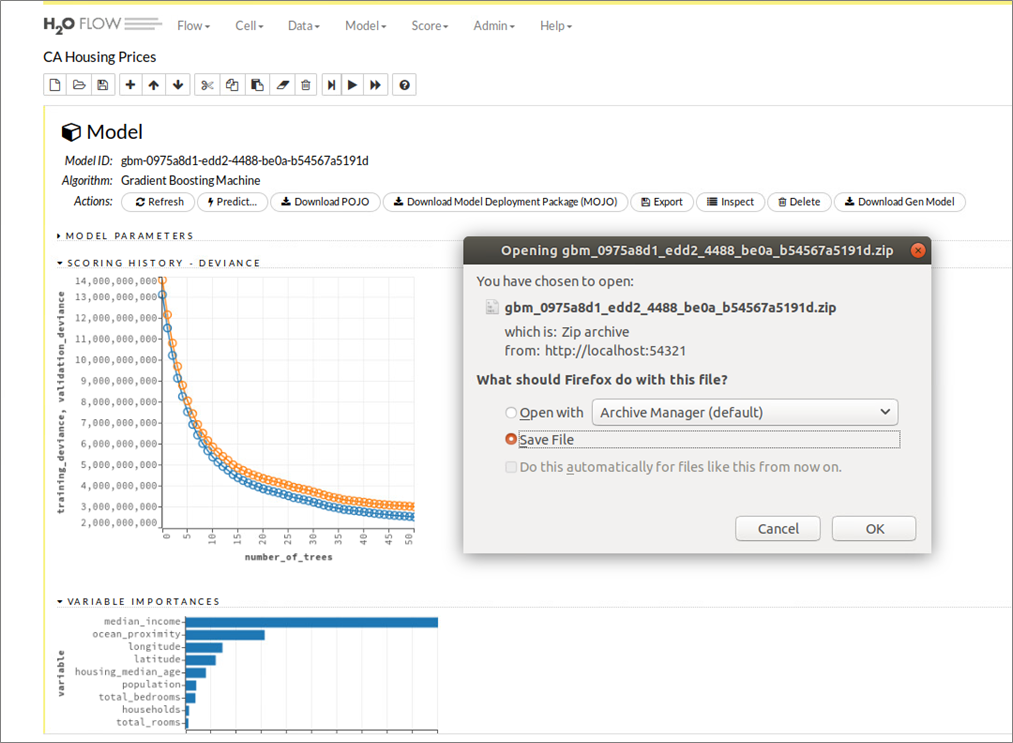

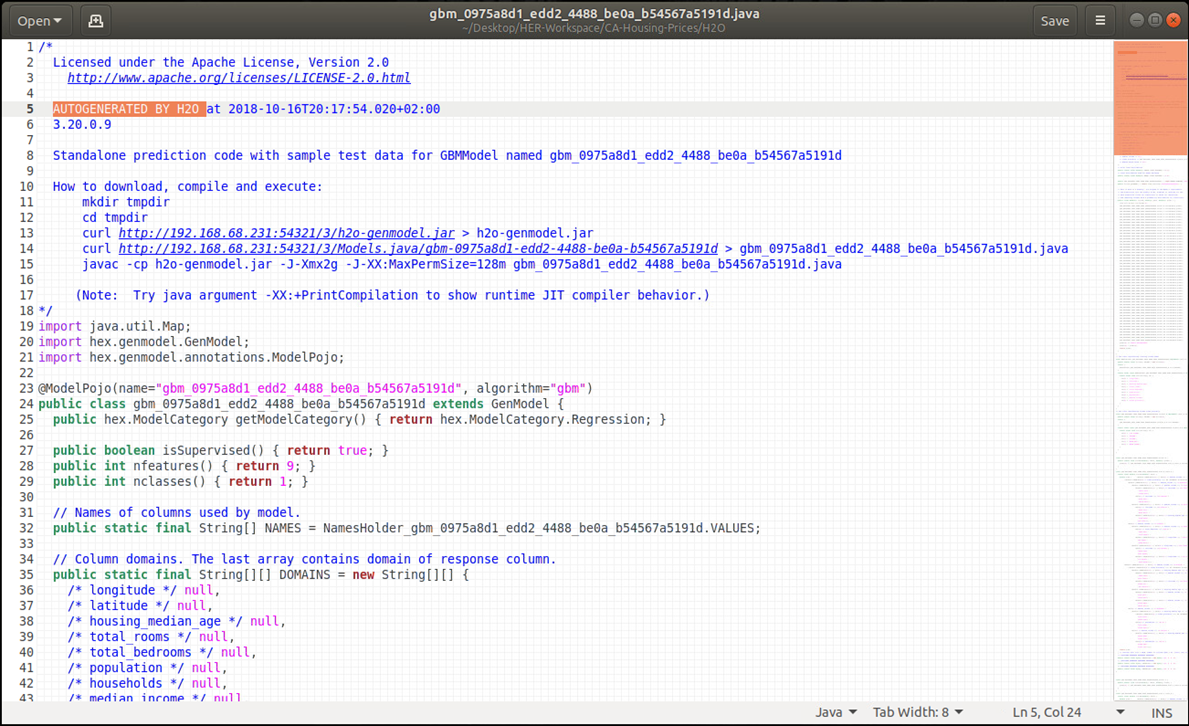

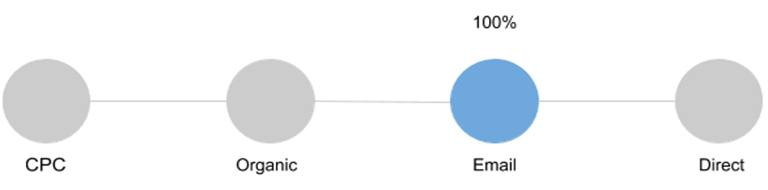

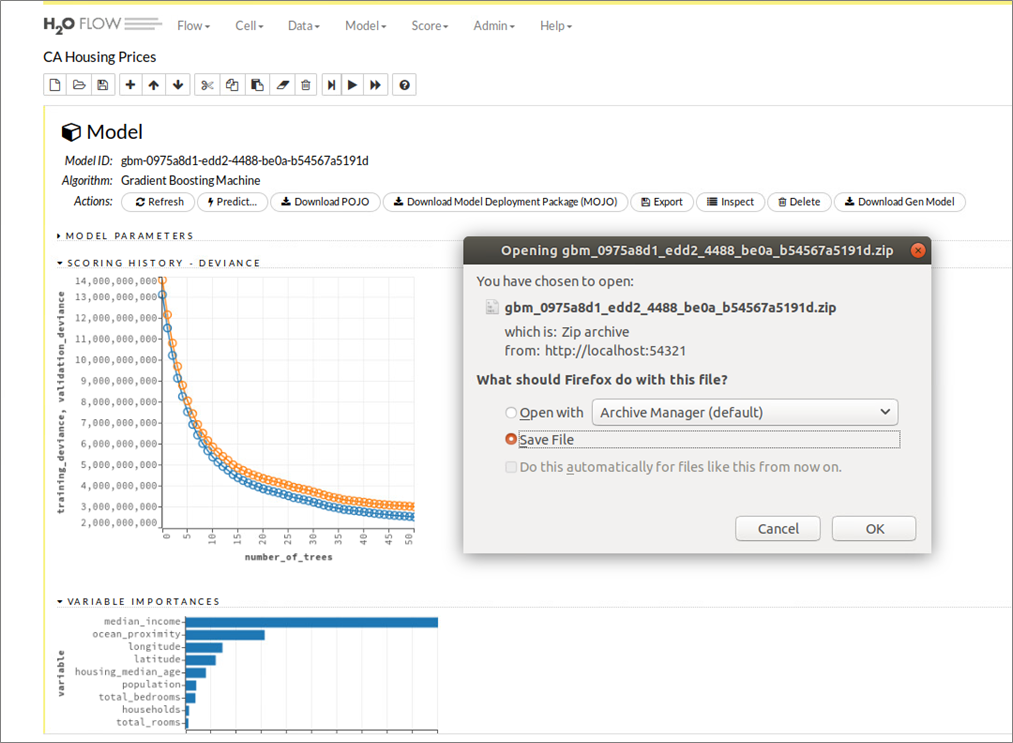

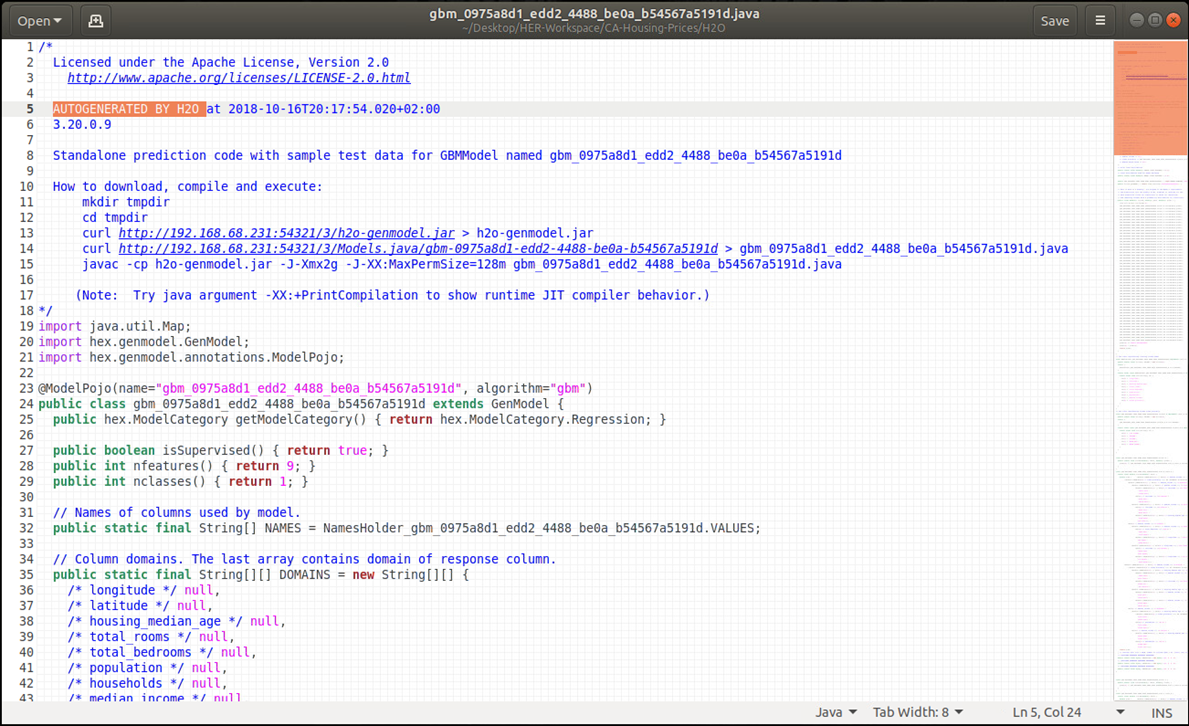

Die Deployment-Variante „Machine Learning Code-Generierung“ lässt sich gut an dem bereits mit H2O Flow besprochenen Beispiel veranschaulichen. Während Bild 9 hierzu die Schritte für Modellaufbau, -training und -test illustriert, zeigt Bild 12 den Download-Vorgang für den zuvor generierten Java-Code zum Aufbau eines ML-Modells zur Vorhersage kalifornischer Hauspreise. In dem generierten Java-Code sind die in H2O Flow vorgenommene Datenaufbereitung sowie alle Konfigurationen für den Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM)-Algorithmus gut nachvollziehbar, Bild 13 gibt mit den ersten Programmzeilen einen ersten Eindruck dazu und erinnert gleichzeitig an den ähnlichen Ansatz der oben mit dem Snowflake Cloud Data Warehouse und dem Tool Xpanse AI bereits beschrieben wurde.

Abbildung 12: H2O Flow Benutzeroberfläche – Java-Code Generierung und Download eines trainierten Models

Abbildung 13: Generierter Java-Code eines Gradient Boosted Machine – Modells zur Vorhersage kaliforn. Hauspreise

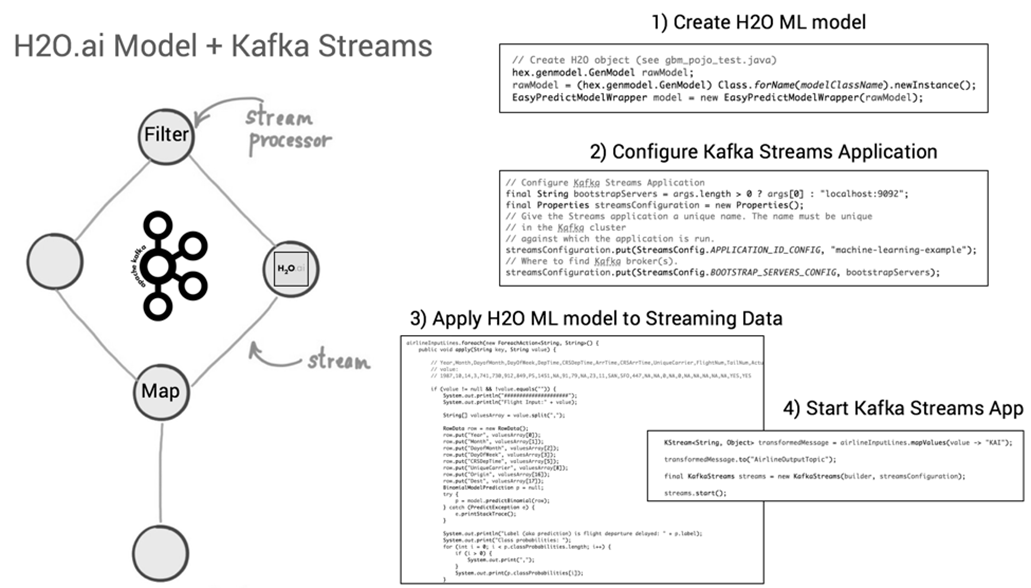

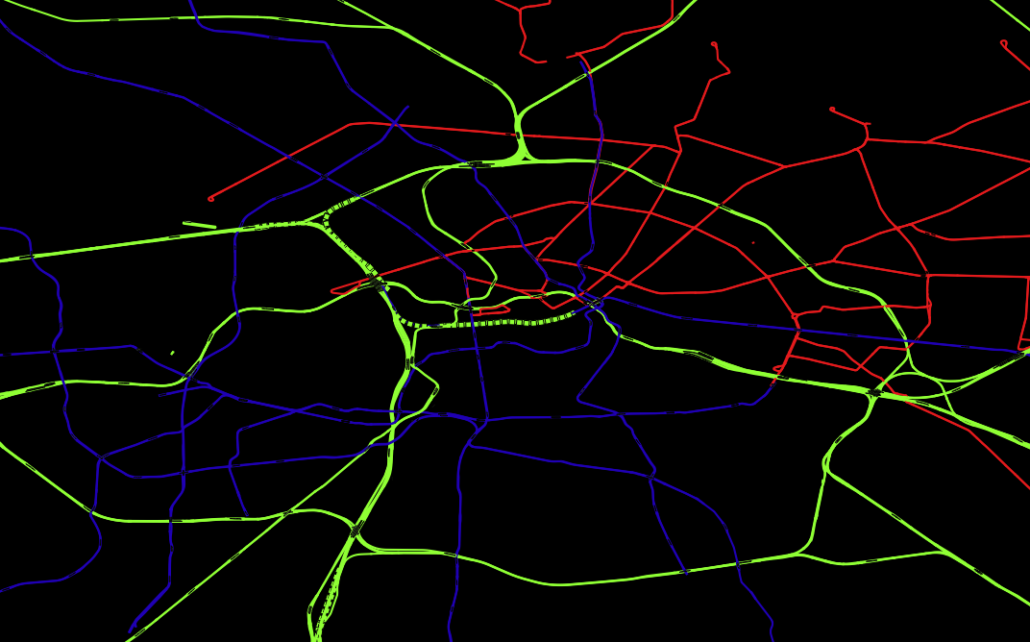

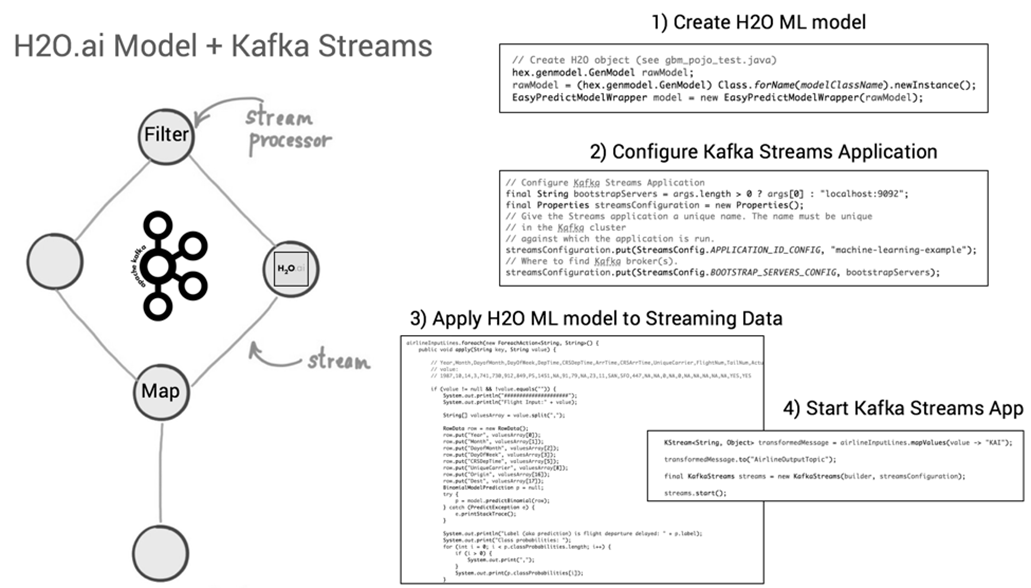

Nach Abschluss der Machine Learning-Entwicklung kann der Java-Code des neuen ML-Modells, z.B. unter Verwendung der Apache Kafka Streams API, zu einer Streaming-Applikation hinzugefügt und publiziert werden [16]. Vorteil dabei: Die Kafka Streams-Applikation ist selbst eine Java-Applikation, in die der generierte Code des ML-Modells eingebettet werden kann (siehe Bild 14). Alle zukünftigen Events, die neue Immobilien-Datensätze zu Häusern aus Kalifornien mit (denselben) Features wie Geoposition, Alter des Gebäudes, Anzahl Zimmer etc. enthalten und als ML-Modell-Input über Kafka Streams hereinkommen, werden mit einer Vorhersage des voraussichtlichen Gebäudepreises von dem auf historischen Daten trainierten ML-Algorithmus beantwortet. Ein Vorteil dabei: Weil die Kafka Streams-Applikation unter der Haube alle Funktionen von Apache Kafka nutzt, ist diese neue Anwendung bereits für den skalierbaren und geschäftskritischen Einsatz ausgelegt.

Abbildung 14: Deployment des generierten Java-Codes eines H2O ML-Models in einer Kafka Streams-Applikation

Machine Learning as a Service – “API-first” Ansatz

In den vorherigen Abschnitten kam bereits die Herausforderung zur Sprache, wenn es um die Überführung der Ergebnisse eines Datenexperiments in eine Produktivumgebung geht. Während die Mehrheit der Mitglieder eines Data Science Teams bevorzugt R, Python (und vermehrt Julia) als Programmiersprache einsetzen, gibt es auf der Abnehmerseite das Team der Softwareingenieure, die für technische Implementierungen in der Produktionsumgebung zuständig sind, womöglich einen völlig anderen Technologie-Stack verwenden (müssen). Im Extremfall droht das Neuimplementieren eines Machine Learning-Modells, im besseren Fall kann Code oder die ML-Modellspezifikation transferiert und mit wenig Aufwand eingebettet (vgl. das Beispiel H2O und Apache Kafka Streams Applikation) bzw. direkt in einer neuen Laufzeitumgebung ausführbar gemacht werden. Alternativ wählt man einen „API-first“-Ansatz und entkoppelt das Zusammenwirken von unterschiedlich implementierten Applikationen bzw. -Applikationsteilen via Web-API’s. Data Science-Teams machen hierzu z.B. die URL Endpunkte ihrer testbereiten Algorithmen bekannt, die von anderen Softwareentwicklern für eigene „smarte“ Applikationen konsumiert werden. Durch den Aufbau von REST-API‘s kann das Data Science-Team den Code ihrer ML-Modelle getrennt von den anderen Teams weiterentwickeln und damit eine Arbeitsteilung mit klaren Verantwortlichkeiten herbeiführen, ohne Teamkollegen, die nicht am Machine Learning-Aspekt des eines Projekts beteiligt sind, bei ihrer Arbeit zu blockieren.

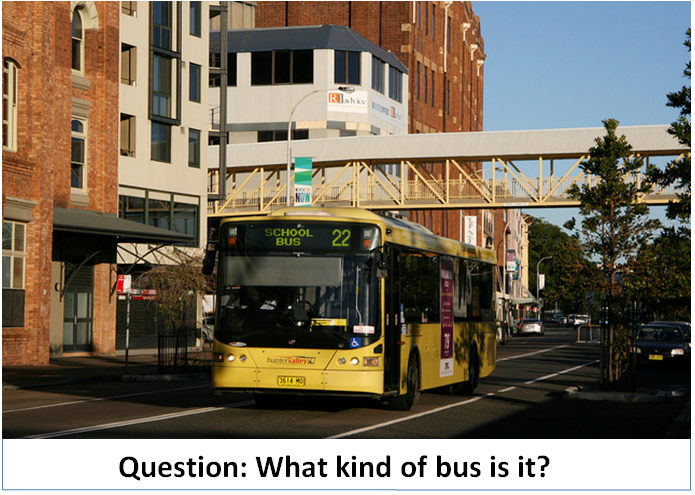

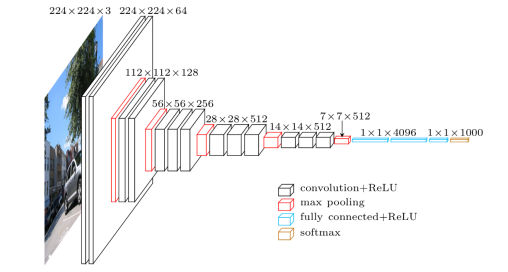

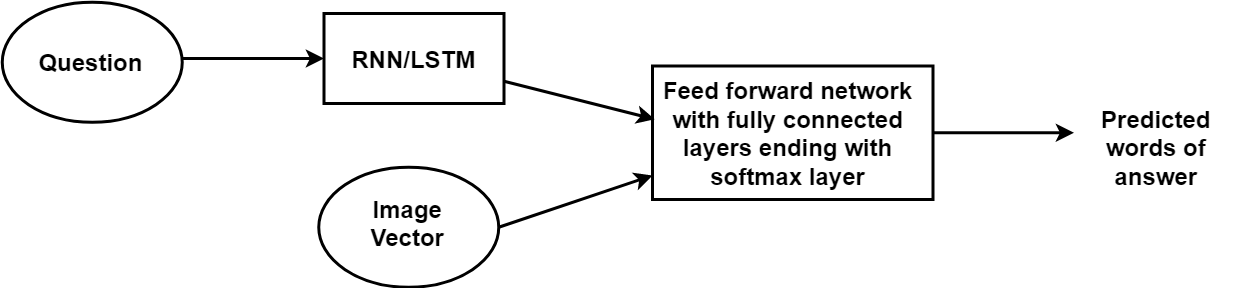

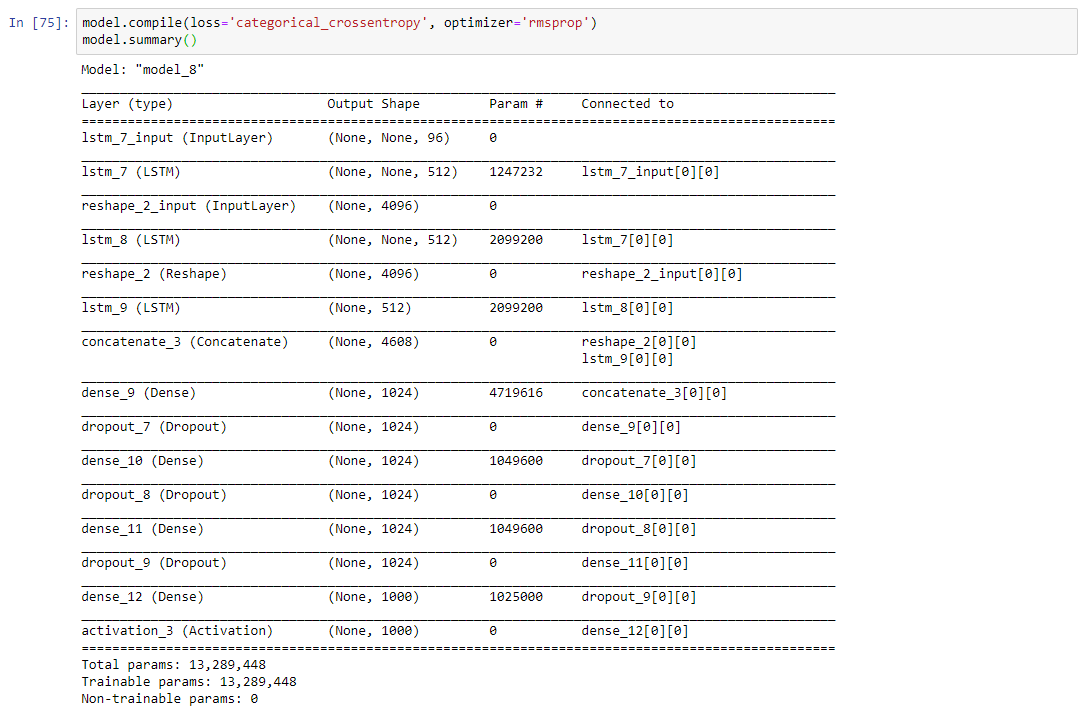

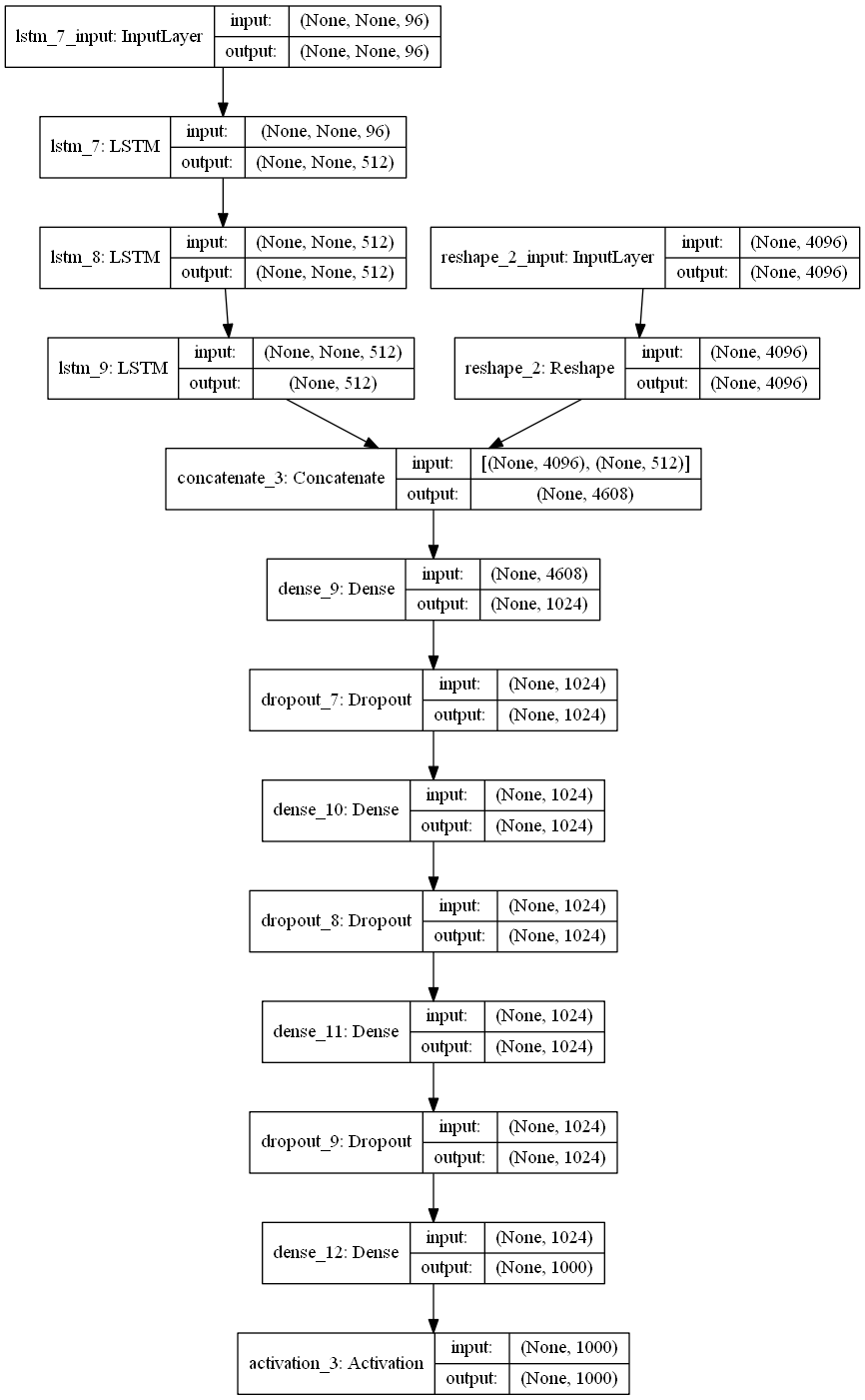

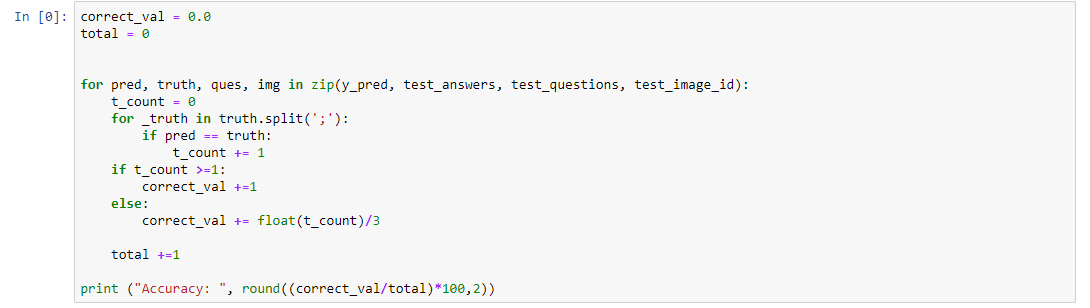

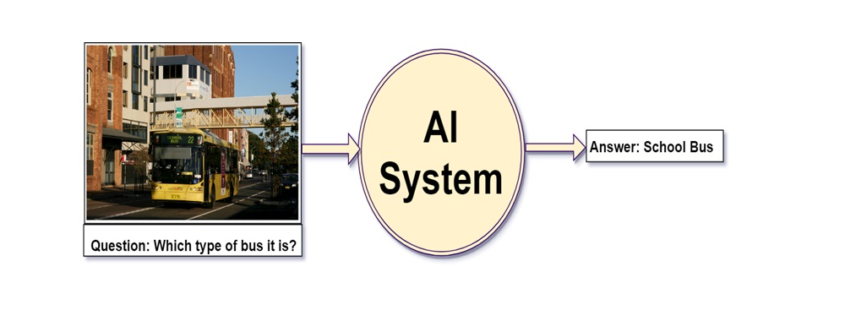

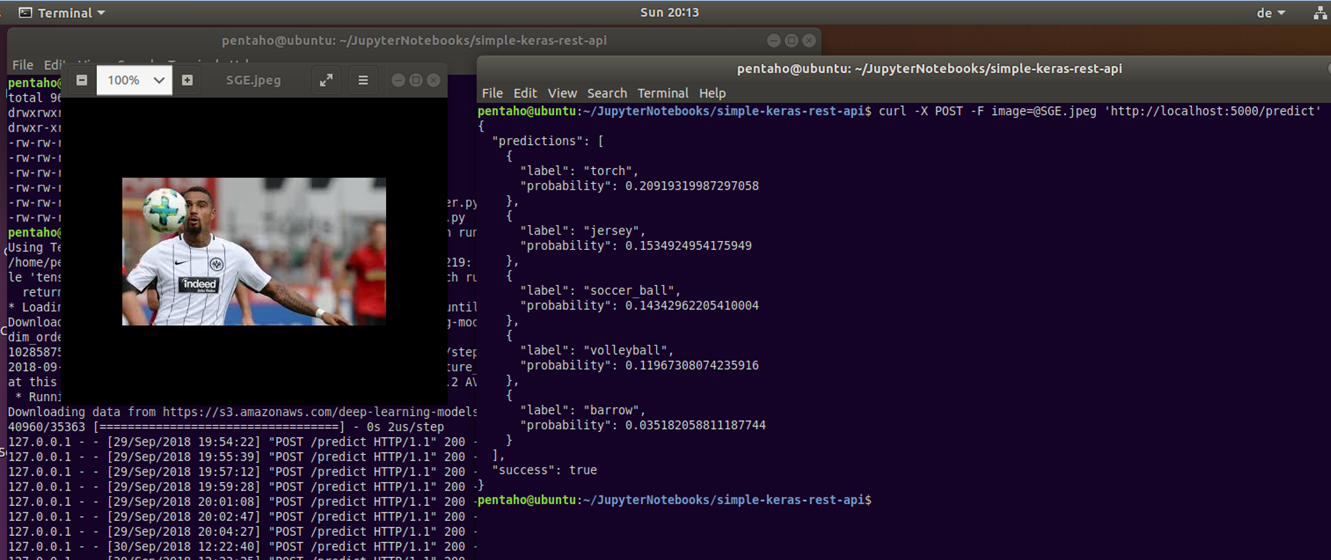

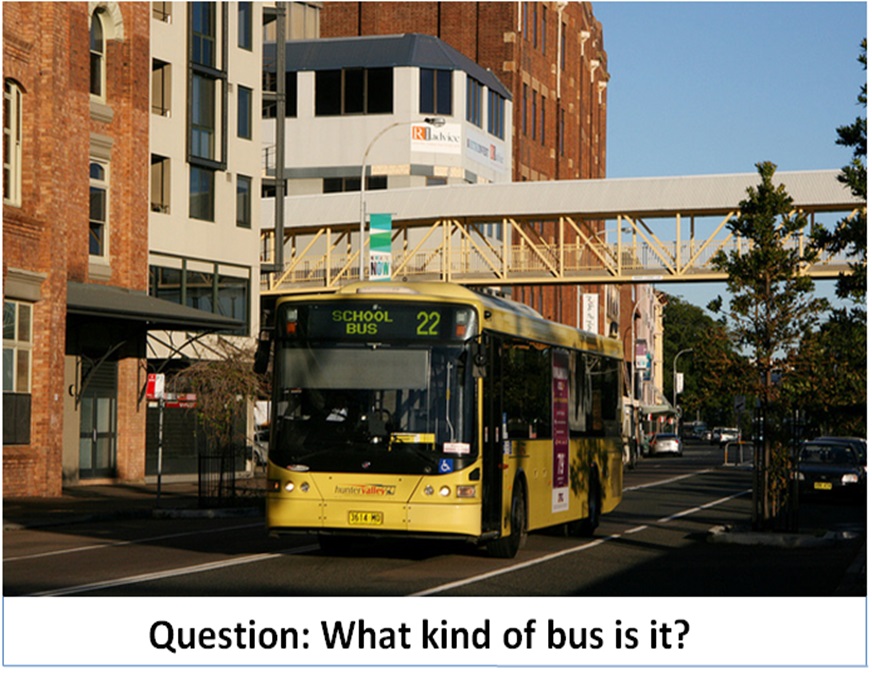

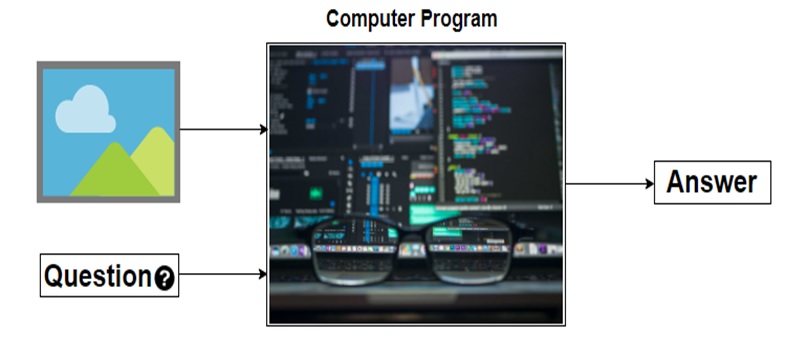

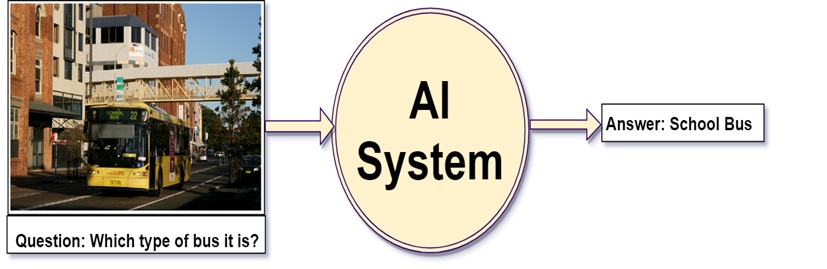

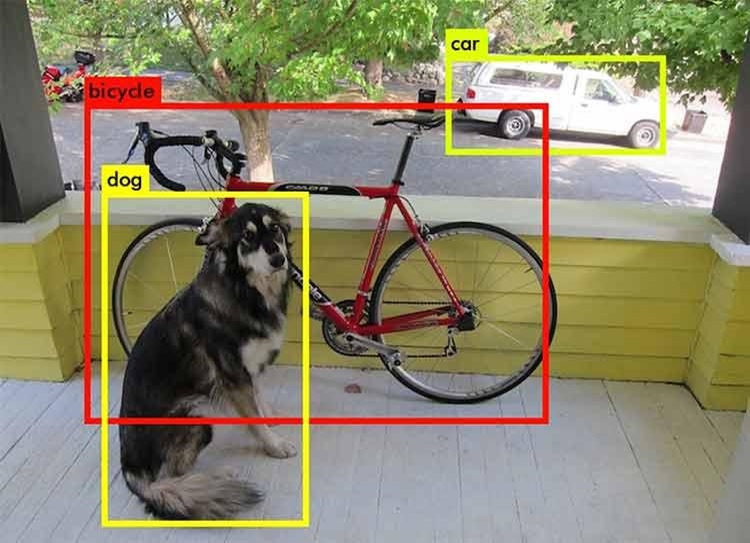

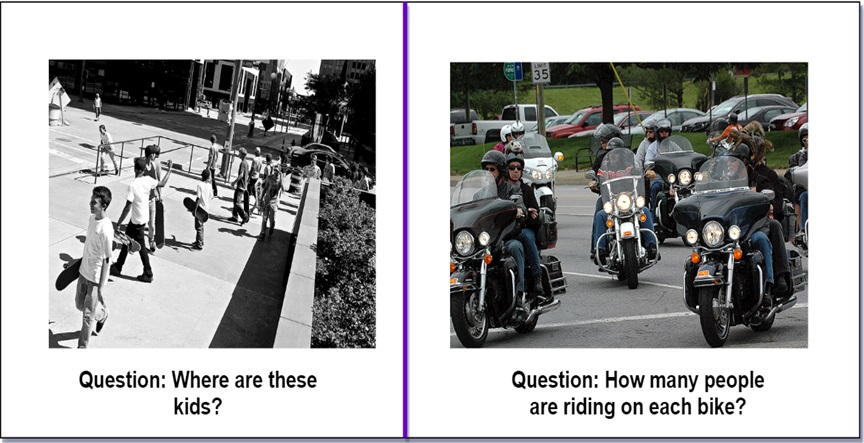

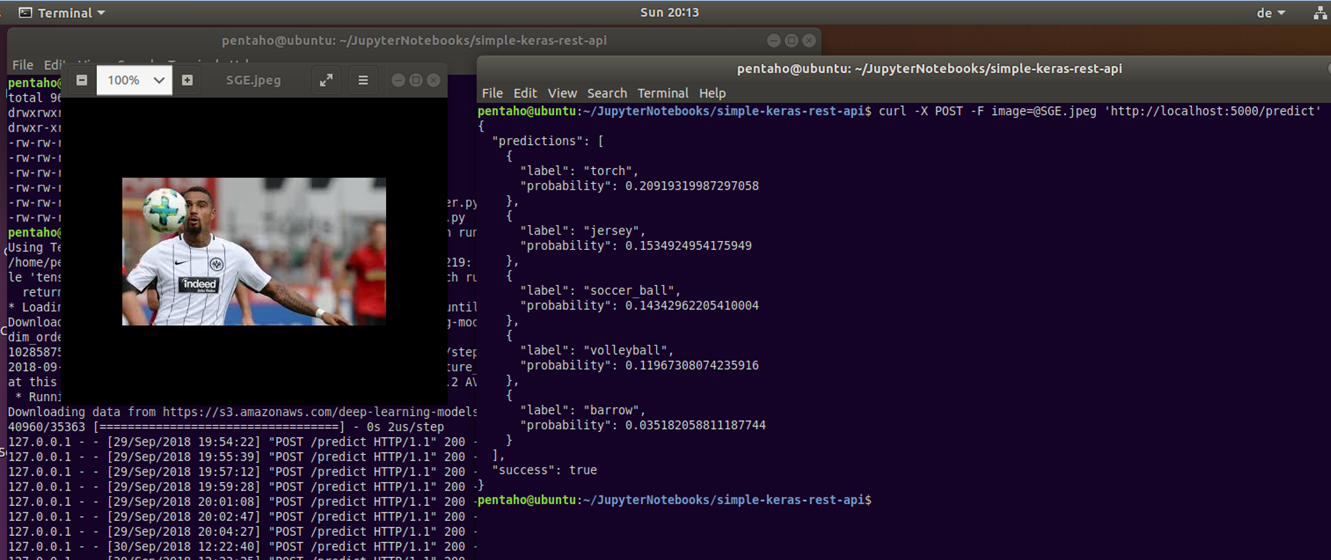

Bild 15 zeigt ein einfaches Szenario, bei dem die Gegenstandserkennung von beliebigen Bildern mit einem Deep Learning-Verfahren umgesetzt ist. Einzelne Fotos können dabei via Kommandozeileneditor als Input für die Bildanalyse an ein vortrainiertes Machine Learning-Modell übermittelt werden. Die Information zu den erkannten Gegenständen inkl. Wahrscheinlichkeitswerten kommt dafür im Gegenzug als JSON-Ausgabe zurück. Für die Umsetzung dieses Beispiels wurde in Python auf Basis der Open Source Deep-Learning-Bibliothek Keras, ein vortrainiertes ML-Modell mit Hilfe des Micro Webframeworks Flask über eine REST-API aufrufbar gemacht. Die in [17] beschriebene Applikation kümmert sich außerdem darum, dass beliebige Bilder via cURL geladen, vorverarbeitet (ggf. Wandlung in RGB, Standardisierung der Bildgröße auf 224 x 224 Pixel) und dann zur Klassifizierung der darauf abgebildeten Gegenstände an das ML-Modell übergeben wird. Das ML-Modell selbst verwendet eine sog. ResNet50-Architektur (die Abkürzung steht für 50 Layer Residual Network) und wurde auf Grundlage der öffentlichen ImageNet Bilddatenbank [18] vortrainiert. Zu dem ML-Modell-Input (in Bild 15: Fußballspieler in Aktion) meldet das System für den Tester nachvollziehbare Gegenstände wie Fußball, Volleyball und Trikot zurück, fragliche Klassifikationen sind dagegen Taschenlampe (Torch) und Schubkarre (Barrow).

Abbildung 15: Gegenstandserkennung mit Machine Learning und vorgegebenen Bildern via REST-Service

Bei Aufbau und Bereitstellung von Machine Learning-Funktionen mittels REST-API’s bedenken IT-Architekten und beteiligte Teams, ob der Einsatzzweck eher Rapid Prototyping ist oder eine weitreichende Nutzung unterstützt werden muss. Während das oben beschriebene Szenario mit Python, Keras und Flask auf einem Laptop realisierbar ist, benötigen skalierbare Deep Learning Lösungen mehr Aufmerksamkeit hinsichtlich der Deployment-Architektur [19], in dem zusätzlich ein Message Broker mit In-Memory Datastore eingehende bzw. zu analysierende Bilder puffert und dann erst zur Batch-Verarbeitung weiterleitet usw. Der Einsatz eines vorgeschalteten Webservers, Load Balancers, Verwendung von Grafikprozessoren (GPUs) sind weitere denkbare Komponenten für eine produktive ML-Architektur.

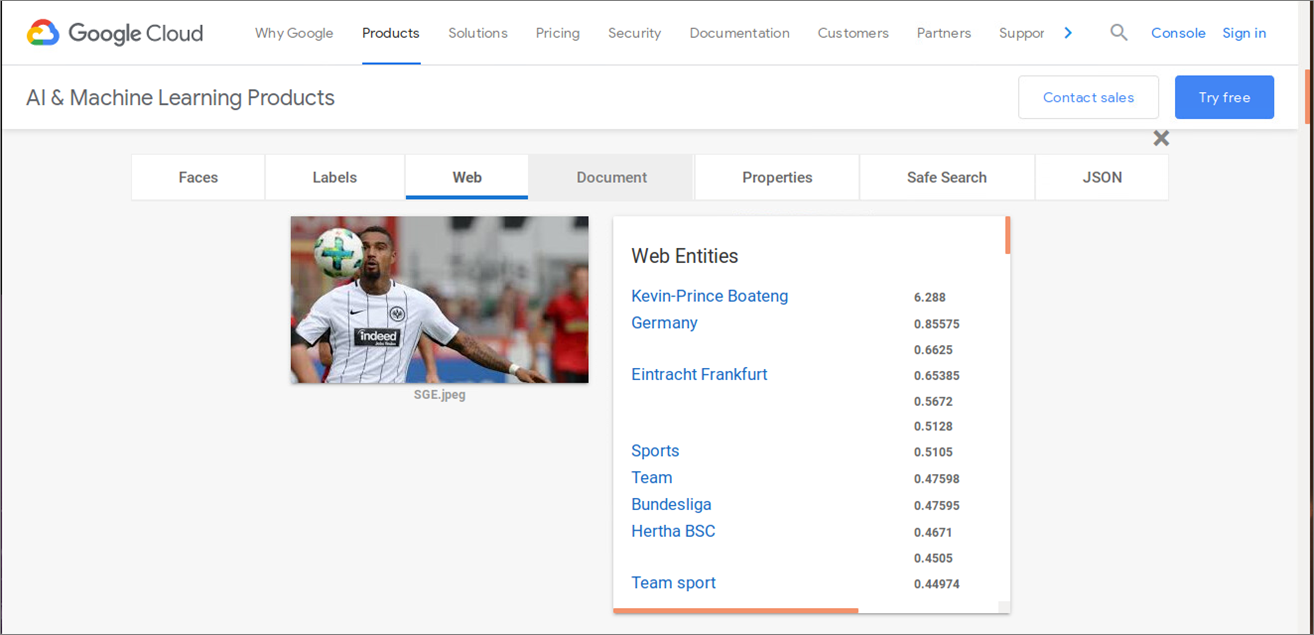

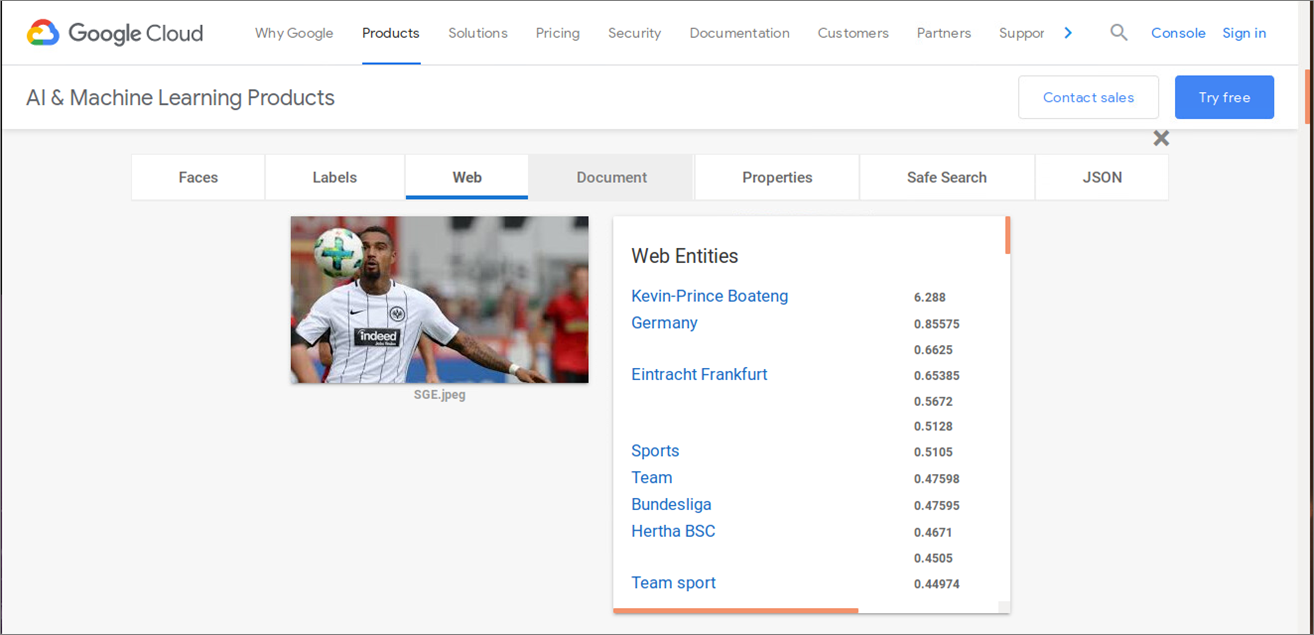

Als abschließendes Beispiel für einen leistungsstarken (und kostenpflichtigen) Machine Learning Service soll die Bildanalyse von Google Cloud Vision [20] dienen. Stellt man dasselbe Bild mit der Fußballspielszene von Bild 15 und Bild 16 bereit, so erkennt der Google ML-Service neben den Gegenständen weit mehr Informationen: Kontext (Teamsport, Bundesliga), anhand der Gesichtserkennung den Spieler selbst und aktuelle bzw. vorherige Mannschaftszugehörigkeiten usw. Damit zeigt sich am Beispiel des Tech-Giganten auch ganz klar: Es kommt vorallem auf die verfügbaren Trainingsdaten an, inwieweit dann mit Algorithmen und einer dazu passenden Automatisierung (neue) Erkenntnisse ohne langwierigen und teuren manuellen Aufwand gewinnen kann. Einige Unternehmen werden feststellen, dass ihr eigener – vielleicht einzigartige – Datenschatz einen echten monetären Wert hat?

Abbildung 16: Machine Learning Bezahlprodukt (Google Vision)

Fazit

Machine Learning ist eine interessante “Challenge” für Architekten. Folgende Punkte sollte man bei künftigen Initativen berücksichtigen:

- Finden Sie das richtige Geschäftsproblem bzw geeignete Use Cases

- Identifizieren und definieren Sie die Einschränkungen (Sind z.B. genug Daten vorhanden?) für die zu lösende Aufgabenstellung

- Nehmen Sie sich Zeit für das Design von Komponenten und Schnittstellen

- Berücksichtigen Sie frühzeitig mögliche organisatorische Gegebenheiten und Einschränkungen

- Denken Sie nicht erst zum Schluss an die Produktivsetzung Ihrer analytischen Modelle oder Machine Learning-Produkte

- Der Prozess ist insgesamt eine Menge Arbeit, aber es ist keine Raketenwissenschaft.

Quellenverzeichnis

| [1] |

Bill Schmarzo: “What’s the Difference Between Data Integration and Data Engineering?”, LinkedIn Pulse -> Link, 2018 |

| [2] |

William Vorhies: “CRISP-DM – a Standard Methodology to Ensure a Good Outcome”, Data Science Central -> Link, 2016 |

| [3] |

Bill Schmarzo: “A Winning Game Plan For Building Your Data Science Team”, LinkedIn Pulse -> Link, 2018 |

| [4] |

D. Sculley, G. Holt, D. Golovin, E. Davydov, T. Phillips, D. Ebner, V. Chaudhary, M. Young, J.-F. Crespo, D. Dennison: “Hidden technical debt in Machine learning systems”. In NIPS’15 Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems – Volume 2, 2015 |

| [5] |

K. Bollhöfer: „Data Science – the what, the why and the how!“, Präsentation von The unbelievable Machine Company, 2015 |

| [6] |

Carlton E. Sapp: “Preparing and Architecting for Machine Learning”, Gartner, 2017 |

| [7] |

A. Geron: “California Housing” Dataset, Jupyter Notebook. GitHub.com -> Link, 2018 |

| [8] |

R. Fehrmann: “Connecting a Jupyter Notebook to Snowflake via Spark” -> Link, 2018 |

| [9] |

E. Ma, T. Grabs: „Snowflake and Spark: Pushing Spark Query Processing to Snowflake“ -> Link, 2017 |

| [10] |

Dr. D. James: „Entscheidungsmatrix „Machine Learning“, it-novum.com -> Link, 2018 |

| [11] |

Oracle Analytics@YouTube: “Oracle DV – ML Model Comparison Example”, Video -> Link |

| [12] |

J. Weakley: Machine Learning in Snowflake, Towards Data Science Blog -> Link, 2019 |

| [13] |

Dr. S. Sayad: An Introduction to Data Science, Website -> Link, 2019 |

| [14] |

U. Bethke: Build a Predictive Model on Snowflake in 1 day with Xpanse AI, Blog à Link, 2019 |

| [15] |

Sergei Izrailev: Design Patterns for Machine Learning in Production, Präsentation H2O World, 2017 |

| [16] |

K. Wähner: How to Build and Deploy Scalable Machine Learning in Production with Apache Kafka, Confluent Blog -> Link, 2017 |

| [17] |

A. Rosebrock: “Building a simple Keras + deep learning REST API”, The Keras Blog -> Link, 2018 |

| [18] |

Stanford Vision Lab, Stanford University, Princeton University: Image database, Website -> Link |

| [19] |

A. Rosebrock: “A scalable Keras + deep learning REST API”, Blog -> Link, 2018 |

| [20] |

Google Cloud Vision API (Beta Version) -> Link, abgerufen 2018 |